Chapter 12:

Preaudits & Disbursements

12.0 Introduction

Article V, Section 7(2) of the North Carolina Constitution provides that “[n]o money shall be drawn from the treasury of any county, city or town, or other unit of local government except by authority of law.” The Local Government Budget and Fiscal Control Act (LGBFCA) establishes the requirements regarding the disbursement of public funds. Through both the budget ordinance and project ordinances, a governing board authorizes the local unit to undertake programs or projects and to spend moneys. (For information on the annual budget ordinance and project ordinances, see Chapter 2, “Budgeting.”) “[N]o local government or public authority may expend any moneys . . . except in accordance with a budget ordinance or project ordinance . . ..” (G.S. 159-8). The proper functioning of the budgeting process depends on adherence to the terms of the budget ordinance and any project ordinances.

The principal legal mechanisms for ensuring compliance with the budget ordinance and each project ordinance are the preaudit and disbursement processes prescribed by the LGBFCA. Both processes are set forth in G.S. 159-28. The statute also specifies the forms of payment that a local unit may use to satisfy its obligations.

12.1 The Preaudit Requirement

G.S. 159-28(a), (a1), and (a2), collectively referred to as the preaudit requirement, state as follows:

(a) Incurring Obligations. – No obligation may be incurred in a program, function, or activity accounted for in a fund included in the budget ordinance unless the budget ordinance includes an appropriation authorizing the obligation and an unencumbered balance remains in the appropriation sufficient to pay in the current fiscal year the sums obligated by the transaction for the current fiscal year. No obligation may be incurred for a capital project or a grant project authorized by a project ordinance unless that project ordinance includes an appropriation authorizing the obligation and an unencumbered balance remains in the appropriation sufficient to pay the sums obligated by the transaction. Nothing in this section shall require a contract to be reduced to writing.

(a1) Preaudit Requirement. – If an obligation is reduced to a written contract or written agreement requiring the payment of money, or is evidenced by a written purchase order for supplies and materials, the written contract, agreement, or purchase order shall include on its face a certificate stating that the instrument has been preaudited to assure compliance with subsection (a) of this section. The certificate, which shall be signed by the finance officer, or any deputy finance officer approved for this purpose by the governing board, shall take substantially the following form:

“This instrument has been preaudited in the manner required by the Local Government Budget and Fiscal Control Act.

______________________________________________________

(Signature of finance officer [or deputy finance officer]).”

(a2) Failure to Preaudit. – An obligation incurred in violation of subsection (a) or (a1) of this section is invalid and may not be enforced. The finance officer shall establish procedures to assure compliance with this section, in accordance with any rules adopted by the Local Government Commission.

To fully understand the preaudit requirement, it is helpful to break the analysis down into three parts— (1) determining when the statutory provisions apply, (2) determining what the statute requires, and (3) determining what happens if the requirements are not met.

12.2 When Does the Preaudit Requirement Apply?

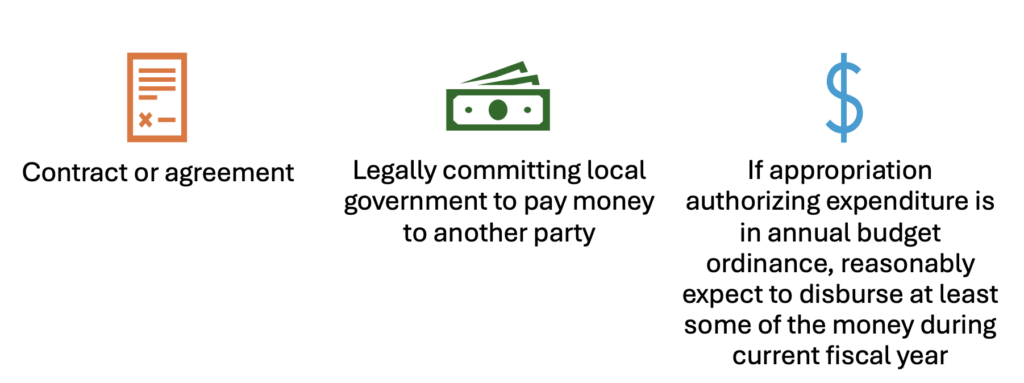

G.S. 159-28(a) applies when a local unit incurs an obligation that is accounted for in the budget ordinance or a project ordinance. An obligation is incurred when a unit commits to pay money to another entity. Examples include placing orders for supplies and equipment, entering into contracts for services, and even hiring employees. In a nutshell, a preaudit is required when all of the following criteria are met:

12.2.1 No Minimum Contract Amount

There is no minimum threshold amount to trigger the requirement. An obligation is incurred if a contract, purchase order, or other agreement commits the unit to an expenditure of any amount.

12.2.2 Contracts with an Uncertain Total Amount

It also does not matter if the total contract amount is uncertain. In Transportation Services of N.C., Inc. v. Wake County Board. of Education, 198 N.C. App. 590, 596-98 (2009), the court of appeals held that a contract in which the school board agreed to compensate transportation services provider for services on a per-student-assigned basis was subject to preaudit requirement under an analogous provision to G.S. 159-28. Similarly, in Watauga County Board of Education v. Town of Boone, 106 N.C. App. 270, 276 (1992), the court held that a resolution passed by the town requiring that 18 percent of the profits of the town’s ABC store be given to the school system was subject to preaudit requirement even though the total amount of the obligation was uncertain. Based on the reasoning in these cases, requirement contracts for goods, whereby the local unit agrees to purchase all the goods it needs from the vendor during a specified period at a pre-negotiated price, and hourly contracts for services are subject to preaudit. The finance officer must preaudit based on a reasonable estimate of the total amount to be paid out.

12.2.3 Form of Contract

The form of the obligation also is irrelevant. A local unit may incur an obligation by executing a construction contract, issuing an electronic purchase order for goods, or verbally committing to pay a salary to a newly hired at-will employee.

12.2.4 Specific Performance Obligations

A preaudit is not required unless a unit enters into a contract or agreement that commits the unit to pay money. An example is an agreement by a municipality to provide water to a commercial entity located outside its borders. Such a contract commits the unit to perform a specific task; it does not, however, commit the unit to pay money. This type of arrangement is often referred to as a contract for specific performance, and it does not trigger the preaudit. [Compare Lee v. Wake Cnty., 165 N.C. App. 154 (2004) (holding that agreement to enter into a formal settlement agreement did not require preaudit because it was “an action for specific performance, not for the payment of money”), and Moss v. Town of Kernersville, No. COA01-194, 2002 WL 1166581, (N.C. App. June 4, 2002) (holding that consent agreement, whereby the town agreed to make certain repairs to a dam, did not require a preaudit certificate because it was a contract for specific performance, not a contract requiring the payment of money), with Cabarrus Cnty. v. Systel Bus. Equip. Co., 171 N.C. App. 423 (2005) (holding that the settlement agreement at issue, which required the county to pay a specified amount of money, required preaudit)].

12.2.5 Continuing (Multi-Year) Contracts

What about continuing contracts— those extending more than one fiscal year? Whether or not the preaudit is triggered depends in part on whether the appropriation authorizing the obligation is accounted for in the annual budget ordinance or a project ordinance.

Annual Budget Ordinance Appropriations

If the appropriation authorizing the obligation is accounted for in the annual budget ordinance and the unit will certainly have to expend money under the contract in the fiscal year in which it is entered into, an obligation is incurred for purposes of G.S. 159-28(a). If, however, a local unit does not expect to expend money in the current fiscal year, things get a little murkier. There are a couple of court of appeals cases suggesting that if there is a good chance that no resources will be expended in the year in which the contract or agreement is entered into, then a preaudit is not needed. In Myers v. Town of Plymouth, 135 N.C. App. 707 (1999); the town entered an employment contract with the town manager in March 1997 (fiscal year 1996–97), whereby the manager agreed to work for the town for four years. Both the town and the manager reserved the right to terminate the employment relationship with thirty days’ notice. The contract provided the manager with a severance package if he was terminated by the town for any reason except felonious criminal conduct or a failure of performance that the manager failed to rectify after appropriate notice. The following December (fiscal year 1997–98), a new town council was seated, and within a few months, the new council terminated the manager and refused to pay the severance package. The manager sued. Among other defenses, the town argued that the employment contract was void because it lacked a preaudit certificate [one of the requirements of G.S. 159-28(a)]. The court disagreed, holding that no preaudit was needed because it was highly improbable that the town would have been required to pay the severance package in the fiscal year in which the contract was signed. (The town was not required to pay the severance package in the fiscal year in which the contract was signed.) [See also M Series Rebuild, LLC v. Town of Mount Pleasant, 222 N.C. App. 59 (2012), review denied, 366 N.C. 413 (2012) (noting that preaudit required a “contract and obligation to pay [that were] both created in the same fiscal year.”); Davis v. City of Greensboro, 770 F.3d 278 (4th Cir. 2014) (holding the preaudit certificate not required on law enforcement and firefighter longevity pay contracts, where no payments came due during the fiscal year in which the contracts were entered into)].

It is not entirely clear how broadly to read Myers. The holding may be limited to the unique factual scenario presented by this one case. Even if it is meant to be applied more broadly, the holding leaves many unanswered questions. For example, it is not clear how low the probability or possibility of incurring an obligation in the current fiscal year must be for the preaudit requirement not to apply. Given this ambiguity, it may be safer for a unit to comply with G.S. 159-28(a) if there is any chance it will have to expend funds under the contract, agreement, or purchase order in the current fiscal year.

If a preaudit is required for a multi-year contract, the finance officer or deputy finance officer will only be attesting that there is a budget appropriation for the amount expected to come due in the current fiscal year. A unit is not required to re-preaudit the contract in future fiscal years. However, G.S. 159-13(b)(15) generally requires a governing board to appropriate sufficient moneys each year to cover the amounts due that year under continuing contracts.

Project Ordinance Appropriations

If the appropriation authorizing the obligation is accounted for in a capital or grant project ordinance, the preaudit is triggered regardless of whether any amounts are expected to come due in the fiscal year in which the obligation is incurred. [See G.S. 159-28(a)]. A project ordinance is effective for the life of the project. It does not expire at the end of each fiscal year. (G.S. 159-13.2). The preaudit will be for the full amount of the obligation. [See G.S. 159-28(a)].

12.2.6 Master Contracts

Sometimes, a local unit will execute a master contract with a vendor or contractor that covers the general terms of the relationship. It binds the parties to work with each other but does not reflect a legal obligation for the local unit to pay money to the other party. Instead, individual purchase orders (POs) or other sub-contracts are issued based on the master. These contracts commit the local government to pay money in exchange for specified goods or services, meaning these POs or other sub-contracts must be preaudited, not the master contract.

12.2.7 Electronic Transactions

Finally, what about when a unit places an Internet order for park equipment and pays for the equipment with a credit card? Or when a unit makes a p-card (purchase card) purchase from a local vendor for water treatment chemicals? Or when an ambulance crew member uses a fuel card at a local gas station? Do electronic payment transactions such as these require a preaudit?

The answer is “yes”; the preaudit requirements apply to these transactions. An obligation is incurred for purposes of the preaudit statute in a credit card transaction when a unit uses the credit card, p-card, or fuel card to pay for goods or services. That is when the unit authorizes the issuing company to pay the vendor or contracting party, thereby committing the unit to pay money (to the issuing company) to cover the costs of the expenditure. When the General Assembly authorized local units to make “electronic payments” (defined as payment by charge card, credit card, debit card, or by electronic funds transfer), it specified that each electronic payment “shall be subject to the preaudit process. . ..” [G.S. 159-28(d2)]. As discussed below, a local unit must comply with any rules adopted by the LGC in executing electronic payments. The LGC rules ensure that the local unit properly performs the preaudit process before undertaking an electronic transaction.

12.3 What Does the Preaudit Require?

Before a local unit incurs an obligation subject to the preaudit, the finance officer (or a deputy finance officer approved by the unit’s governing board for this purpose) must perform the following three steps:

- Ensure there is a budget or project ordinance appropriation authorizing the obligation. [G.S. 159-28(a)]. This typically is not much of a hurdle because the budget ordinance and project ordinances are often adopted at a general level of legal control. Units are authorized to make budget appropriations only by department, function, or project. (The preaudit is not performed on line-item appropriations in the unit’s “working budget.”)

- Ensure that sufficient funds will remain in the appropriation to pay the amounts expected to come due. [G.S. 159-28(a)]. If the obligation is accounted for in the annual budget ordinance, the appropriation need cover only the amount expected to come due in the current fiscal year. However, if the obligation is accounted for in a project ordinance, the appropriation must be for the full amount due under the contract.

- If the order, contract, or agreement is in writing, affix and sign a preaudit certificate to the “writing.” [G.S. 159-28(a1)]. If the order, contract, or agreement is not in writing—such as telephone orders or other verbal agreements—a preaudit certificate is not required. (Note, other legal provisions may require a particular contract or agreement to be in writing. For example, all contracts entered into by a municipality must be in writing, though the governing board may ratify a contract that violates this provision. (G.S. 160A-16). All contracts involving the sale of “goods” for $500 or more must be in writing. (G.S. 25-2-201). And contracts for purchases and construction or repair subject to formal bidding requirements must be in writing. [G.S. 143-129(c)]. In addition, as discussed below, a few types of transactions may be exempt from the preaudit certificate requirement, even if they are in writing.

12.3.1 Complying with Preaudit Requirement

The statute envisions all these steps be performed before the obligation is incurred—before the goods are ordered or the contract is executed. It is not sufficient to perform the preaudit process after a contract is executed. As numerous finance officers have attested, complying with these requirements can be very difficult.

G.S. 159-28(a2) directs a unit’s finance officer to “establish procedures to assure compliance” with the statute. Thus, a finance officer has flexibility to design ordering and contracting processes that comply with the statute (or at least come close.) The processes likely will vary depending on the size of the unit, the number of personnel, and the various departments’ needs.

One important tool often overlooked by units is statutory authority for the governing board to appoint one or more deputy finance officers to perform the preaudit process. [G.S. 159-28(a1)]. To the extent that individual departments in a unit must order goods or enter into service contracts, the governing board can appoint one or more department heads (or other department employees) as deputy finance officers. The deputy finance officers then would be authorized to enter into obligations consistent with their department budget appropriations.

Even if all ordering/contracting is centralized within the finance office, it may be impossible for the finance officer to perform the preaudit process for each obligation. Again, the governing board could appoint other finance office employees as deputy finance officers to perform the preaudit. [See G.S. 159-28(a1)]. The finance officer also could delegate the ministerial job of performing the preaudit process, including affixing the finance officer’s signature to the preaudit certificate. Under the latter approach, the finance officer must trust that the preaudit process will be properly performed because the finance officer could be held liable for any statutory violations.

12.3.2 Exemptions from Preaudit Certificate Requirement

Recognizing these practical difficulties, the legislature has exempted certain transactions from the preaudit certificate requirement, even if the order, contract, or agreement is in writing. There are three categories of exempt transactions. The first two apply automatically. The third applies only if the LGC adopts certain rules and the local unit follows those rules. And the fourth applies only if the LGC certifies that a local government’s accounting system meets the statutory requirements. (It is worth emphasizing all these exemptions apply only to the preaudit certificate requirement. A unit must perform the other preaudit steps before incurring an obligation pursuant to one or more exempt transactions.)

Exemption 1: Any obligation or document approved by the LGC. [G.S. 159-28(f)(1)]. This exemption from the preaudit certificate requirement applies to loan agreements, debt issuances, and other leases and financial transactions that are subject to LGC approval and have been so approved. It also likely applies to audit contracts, which must be approved by the LGC pursuant to G.S. 159-34. (Here is more information on contracts subject to LGC approval.)

Exemption 2: Payroll expenditures, including all benefits for employees of the local unit. [G.S. 159-28(f)(2)]. This exemption ensures that salary and benefit changes for current employees, even if in writing, do not need to include a preaudit certificate.

Exemption 3: Electronic payments, defined as payments made by charge card, credit card, debit card, gas card, or procurement card. [G.S. 159-28(f)(3); G.S. 159-28(g)(2)]. Electronic payments often are the most difficult to preaudit. The point of transaction often occurs off-site or on the vendor’s proprietary software. A local unit, therefore, cannot easily include a signed preaudit certificate. This exemption eliminates the problem. It only applies, however, if the local unit follows the rules adopted by the LGC. The LGC rules are considered a safe harbor. In other words, the law presumes compliance with the statutory preaudit requirements if a finance officer or deputy finance officer follows the LGC rules. The rules must ensure that a local unit properly performs the other steps in the preaudit process before undertaking an electronic transaction. [G.S. 159-28(d2)].

The LGC rules are part of the North Carolina Administrative Code (NCAC). (Title 20, Chapter 03, Section .0409). These rules require the following:

Resolution. The local unit’s governing board must adopt a resolution authorizing the unit to engage in electronic transactions. [20 NCAC 03 .0409(a)(1)]. That resolution authorizes the unit’s employees and officials to use p-cards, credit cards, and/or fuel cards, and it either incorporates (by reference) the unit’s written policies related to the use of those cards or authorizes the finance officer to prepare those policies.

Encumbrance System. State law requires local units that meet certain population thresholds (municipalities with a population over 10,000 and counties with a population over 50,000) to incorporate encumbrance systems into their accounting systems. (G.S. 159-26). All units must implement encumbrance systems to comply with the new LGC regulations. [20 NCAC 03 .0409(a)(2)]. For units under the population thresholds listed above, the encumbrance system does not have to be incorporated into the unit’s accounting system. In fact, for small units, it can be as simple as tracking expenditures against budget appropriations in a spreadsheet or even on index cards. To facilitate individual transactions, though, a unit might want to create a shared electronic document that can be accessed by anyone authorized to make purchases.

Policies and Procedures. The governing board or finance officer must adopt written policies that outline the procedures for using p-cards, credit cards, and/or fuel cards. At a minimum, the policies must provide a process to ensure that before each transaction is made, the individual making the transaction:

- Ensures there is an appropriate budget ordinance or project/grant ordinance appropriation authorizing the obligation, see 20 NCAC 03 .0409(a)(3)(A) (for school units, the reference should be to the budget resolution, see G.S. 115C-441);

- Ensures that sufficient moneys remain in the appropriation to cover the amount expected to be paid out in the current fiscal year (if the expenditure is accounted for in the budget ordinance/resolution) or the entire amount (if the expenditure is accounted for in a project/grant ordinance), 20 NCAC 03 .0409(a)(2)(A);

- Records the amount of the transaction in the unit’s encumbrance system, 20 NCAC 03 .0409(a)(3)(C), or reports the amount to another individual (either within the individual’s department or within the finance department) to encumber; as stated above, in order to comply with this requirement, each unit must have an encumbrance system.

In addition to these requirements, a unit’s p-card, credit card, and/or fuel card policies should address who has custody of the cards, who has access to the cards, what dollar limits are placed on the cards and individual transactions, what expenditure category limits are placed on the cards, and how transactions must be documented for reconciliation with the monthly bills. They should also state the consequences for failure to comply with these policies. The local unit’s finance officer must oversee all electronic payments, and the policies must build sufficient controls to allow the finance officer to carry out his or her duties.

Policies will vary significantly by local unit and by type of transaction. They must address all the different ways in which p-card, credit card, or fuel card transactions may occur and be detailed enough to inform individual employees and officials of the exact steps they must take (and how to take them) before initiating a p-card, credit card, or fuel card transaction. At the same time, they must be flexible enough to allow local officials to carry out their day-to-day responsibilities effectively. Finance officers may be well advised to consult with department heads and others in their units and formulate policies that track existing business practices as much as possible.

These new rules do not supplant the preaudit process in its entirety. They merely provide a workable alternative to affixing the preaudit certificate to an electronic payment. And these policies, alone, may not provide sufficient internal controls. Finance officers are well advised to implement additional controls where misappropriations are more likely to occur.

Training. Once the policies are enacted, the local unit must train all personnel about the policies and procedures to be followed before using a p-card, credit card, or fuel card. [20 NCAC 03 .0409(a)(4)]. Training should be repeated at regular intervals and presented to all new employees and officials early in their tenures. And the local unit’s governing board needs to set an expectation of full compliance with the preaudit policies by all employees and officials.

Quarterly Reports. The local unit’s staff must prepare and present a budget-to-actual statement by fund to the governing board at least quarterly. The statement needs to include budgeted accounts, actual payments made, amounts encumbered, and the amount of the unobligated budget. [20 NCAC 03 .0409(a)(5)]. It is incumbent on the board to gain sufficient training to properly interpret these reports in order to carry out the board’s fiduciary responsibility to the unit.

A local government must follow the new regulations if it uses p-cards, credit cards, and/or fuel cards since it is impossible to affix the signed, preaudit certificate to p-card, credit card, or fuel card transactions. It is not sufficient to perform the preaudit after the transaction is completed. Because a transaction is void if the preaudit is not followed, a local unit must follow the new rules to come into legal compliance.

Exemption 4: Automated Accounting System. A local unit may perform its preaudit process using an automated accounting system. [G.S. 159-28(a3)]. The system must do all the following:

- Embed functionality that determines that there is an appropriation to the department, function code, or project in which the transaction appropriately falls,

- Ensure that unencumbered funds remain in the appropriation to pay out any amounts that are expected to come due during the budgeted period, and

- Provide real-time visibility to budget compliance, alert threshold notifications, and rules-based compliance measures and enforcement.

If a local unit’s accounting system performs these functions, the unit is not required to include a signed preaudit certificate on any contract, agreement, PO or other written evidence of a transaction subject to the preaudit requirement. A local unit’s finance officer must certify to the LGC that the unit’s accounting system meets these requirements within 30 days of the start of each fiscal year. [G.S. 159-28(a4)]. The certification form is available on the NC Department of State Treasurers website. The LGC’s Secretary may reject or revoke the finance officer’s certification if the prior year’s annual audit includes a finding of budgetary noncompliance or if the LGC’s Secretary determines that the automated financial computer system fails to meet the statutory requirements. [G.S. 159-28(a4)].

It is worth emphasizing all these exemptions apply only to the preaudit certificate requirement. A unit must perform the other preaudit steps before incurring an obligation pursuant to one or more exempt transactions.

12.4 Consequences for Not Complying with the Preaudit Requirements

Failure to perform any of the applicable preaudit requirements makes the contract, agreement, or purchase order void. See, e.g., L&S Leasing, Inc. v. City of Winston-Salem, 122 N.C. App. 619 (1996); Cincinnati Thermal Spray, Inc. v. Pender Cnty., 101 N.C. App. 405 (1991). This is the equivalent of saying that it was never entered into to begin with. It does not matter if either or both parties have performed under the contract. The court of appeals has further held that parties may not recover against government entities under a theory of estoppel when a contract is deemed invalid for lack of compliance with the preaudit requirements. See, e.g., Transp. Servs. of N.C., Inc. v. Wake Cnty. Bd. of Educ., 198 N.C. App. 590 (refusing to allow claim against school based on estoppel in the absence of valid contractual agreement because of lack of preaudit certificate); Finger v. Gaston Cnty., 178 N.C. App. 367 (2006) (“To permit a party to use estoppel to render a county contractually bound despite the absence of the [preaudit] certificate would effectively negate N.C. G.S. § 159-28(a).”); Data Gen. Corp. v. Cnty. of Durham, 143 N.C. App. 97 (2001) (“[T]he preaudit certificate requirement is a matter of public record . . . and parties contracting with a county within this state are presumed to be aware of, and may not rely upon estoppel to circumvent, such requirements.”).

The statute also provides that if “an officer or employee [of a local unit] incurs an obligation or pays out or causes to be paid out any funds in violation of [the preaudit statute], that officer or employee, and the sureties on any official bond for that officer or employee, are liable for any sums so committed or disbursed.” [G.S. 159-28(e)]. The governing board must “determine, by resolution, if payment from the official bond shall be sought and if the governing body will seek a judgment from the finance officer or duly appointed deputy finance officer for any deficiencies in the amount.” [G.S. 159-28(e)]. This means that if any officer or employee orders goods or enters into a contract or agreement subject to a preaudit before the process is completed, he or she could be held personally liable by the unit’s governing board for the amounts obligated, even if the unit never actually incurs the expense.

If a finance officer or a deputy finance officer gives a false certificate, he or she also may be held liable for the sums illegally committed or disbursed. It is a Class 3 misdemeanor and may result in forfeiture of office if the finance officer, or a deputy finance officer, knowingly gives a false certificate. [G.S. 159-181(a)].

12.5 A Practical Approach to Preaudit

The preaudit statute dates to the early 1970s—a time in which local governments and public authorities conducted business very differently. The purpose of this requirement is to ensure that staff follow budgetary directives from the board. But it can seem like a cumbersome and even impossible process at times. The following provide a roadmap to help local units navigate the requirements for different types of transactions. A unit’s preaudit policy should address all these obligation types.

1. General Service, Construction, and Real Property Acquisition Contracts

A local unit enters several types of formal, written contracts requiring a structured process to ensure legal and financial compliance. The process includes steps like competitive procurement, board approval, and legal review by the local government’s attorney. It may involve several departments, including the manager or mayor.

A key part of this process is the preaudit. Before a contract is executed, the finance officer or deputy finance officer must review it and perform the preaudit steps. The preaudit certificate must be attached to the contract, signed and dated by the finance officer or deputy finance officer.

The preaudit must be completed before all parties sign the contract. If signed without the preaudit, the contract is void. To prevent this, some local governments include language specifying that the contract is not binding until the preaudit is performed. In this case, the contract may be signed first, with the preaudit completed afterward, as long as the finance officer or deputy signs the certificate, making the contract legally valid.

2. Employee Contracts

Most local government employees are employed at will. At will employment means the employer may terminate the employee at any time, for any reason or no reason at all, as long as it is not for an unlawful reason. Likewise, under the at-will employment doctrine, employees can decide to leave their employer whenever they want, at their discretion.

At will employment agreements are contracts subject to preaudit. That is true even if they are not memorialized in a written employment agreement. A local unit must have a process to preaudit these contracts before they are executed. That means all employment decisions should be routed through finance before offers are made. If a written employment contract is executed, the contract must include the signed preaudit certificate. If there is no written contract, only the first two steps of the preaudit are performed. A local unit should have a written process to ensure the preaudit is performed consistently.

3. Purchase Contracts Above the Purchase Order Threshold

Many local units establish a formal contracting process for purchases above a certain amount. The finance office issues a purchase order (PO) to the vendor or contractor to memorialize the legal agreement. The PO process is the series of steps that ensure goods and services are procured in a legal, efficient, and accountable manner. A PO threshold is the dollar amount of the contract that triggers this formal process. Any contracts at or over that amount must comply with the PO process. A well-defined PO threshold and process help local governments comply with legal requirements, ensure financial control, reduce fraud, and enhance accountability in public procurement. The preaudit must be part of this formal process. It is often easier to coordinate through the finance department to ensure that the preaudit and other required processes are properly performed.

The PO process for local governments is a systematic set of steps to ensure proper and accountable procurement of goods and services. The process ensures that purchases are made in a transparent, efficient, and legally compliant manner, while safeguarding public funds.

Identification of Need. The process begins when a department or division within the local government identifies a need for goods or services, often triggered by operational requirements, projects, or routine maintenance needs. The department head or project manager typically initiates the purchase request, specifying what goods or services are needed.

Request for Purchase (or Purchase Requisition). Once the need is identified, the department will create a Purchase Requisition (PR) to formally request the item or service. For lower-value purchases, this may be done through informal means, such as submitting a requisition form or using a procurement card. However, a more formal requisition process is required when the estimated cost exceeds the established PO threshold. This requisition outlines the specific goods or services needed, including relevant details such as item description, quantity, and any special requirements.

Preaudit Process and Approval of Requisition. The purchase requisition is then submitted to the finance office for review and approval. This step ensures that the requested purchase falls within the department’s approved budget. The finance officer, or a deputy finance officer approved by the board, performs the preaudit process. The review also ensures that the proposed purchase complies with other relevant procurement policies and regulations, preventing unauthorized or excessive spending. For purchases that meet or exceed the established PO threshold, the local government may have to engage in a competitive procurement process. This step may involve issuing a Request for Proposal (RFP) or Request for Quote (RFQ), where vendors are invited to submit bids for the requested goods or services. The competitive bidding process ensures that the government receives the best possible value for public funds, while complying with legal and regulatory requirements.

Issuance of Purchase Order (PO) with Preaudit Certificate. Once the requisition is approved, the next step is the creation of a Purchase Order (PO). A PO is a formal document that authorizes the selected vendor to deliver the requested goods or services under specific terms and conditions. It serves as a legally binding agreement between the local government and the vendor, outlining key details such as the item description, quantity, price, delivery terms, and payment terms. For any purchase exceeding the PO threshold, the issuance of a PO is mandatory, ensuring that all larger transactions are properly documented and tracked. The PO must include the signed preaudit certificate. The certificate may be pre-printed on PO forms, but the finance officer or deputy finance officer only signs after the other preaudit steps are performed.

Order Confirmation and Delivery. Once a vendor is selected and the purchase order is issued, the vendor confirms the order and proceeds with delivering the goods or services. Upon receipt of the order, the designated department or staff verifies that the items match the specifications outlined in the PO and that the correct quantity and quality are delivered. Any discrepancies or issues are promptly reported to the vendor for resolution. This ensures that the local government receives exactly what was ordered and that the vendor has fulfilled the terms of the agreement. Then, the finance office proceeds to the disbursement process (discussed below).

4. Purchase Contracts Below the Purchase Order Threshold

These purchases are the most challenging contracts to preaudit. Purchases of all types are made by staff across many departments. Some purchases might be at local vendors, others at national companies. Some purchases are made in person, others online, and others by phone. Because there is no minimum amount to trigger a preaudit, a local unit must devise processes to address all the common ways goods under the PO threshold are procured. Potential options include:

Automate Budget Monitoring. Implement financial management systems that provide real-time visibility into budget appropriations and expenditures, helping to ensure that funds are available before a commitment is made. As detailed above, a preaudit certificate is not required if a local unit implements an LGC-certified accounting system.

Assign Deputy Finance Officers. Empower deputy finance officers in departments with high purchasing volume to perform the preaudit under the oversight of the finance officer. The governing board must designate specific individuals as deputy finance officers.

Use Blanket POs for Routine Purchases. Blanket Purchase Orders (POs) are pre-approved, long-term purchase agreements that cover a range of purchases over a specific period—usually for recurring goods or services. Rather than issuing a separate purchase order for each transaction, a blanket PO sets an overall budget for a particular vendor or category of goods and services. The agreement specifies a total amount to be spent, often broken down by category or department, and allows multiple orders to be placed under the same PO without needing individual approvals. Blanket POs help manage recurring purchases and ensure that funds are allocated correctly. A local unit can preaudit on the authorized maximum amount for each department for a specified period. The POs are tracked against actual spending to ensure compliance.

Use P-Cards, Credit Cards, and/or Fuel Cards. A local unit can use p-cards, credit cards, and/or fuel cards (collectively, electronic transactions) to make purchases under the PO threshold. (P-cards are a type of credit card government agencies use to make small, routine purchases more efficiently. They are typically issued to employees who need to buy goods and services as part of their job, such as office supplies, travel expenses, or other operational needs.) A unit can program the p-cards, credit cards, and/or fuel cards with transaction limits and expenditure restrictions. By setting maximum transaction limits and monthly spending thresholds, electronic transactions can ensure that individual purchases stay within budgetary constraints. The finance officer preaudits the maximum authorized amount per card for a specified period. Additionally, p-cards and credit cards can be programmed to allow only specific categories of purchases, such as office supplies or travel expenses, and restrict transactions to pre-approved vendors. This minimizes the risk of unauthorized spending and ensures that purchases align with approved budget categories or project ordinances.

Furthermore, electronic transactions can be integrated with the local unit’s financial system. Finance officers or designated deputy finance officers can monitor these transactions in real-time, receive automated alerts for high-value or out-of-scope purchases, and review purchases for compliance. By leveraging p-card, credit card, and fuel card programming in this way, local units can maintain financial oversight, reduce manual preaudit efforts, and ensure all obligations are within legal and budgetary limits.

Training and Awareness. Regular training for departments on the importance of the preaudit process and how to manage purchasing activities within the bounds of the budget and appropriation laws.

12.6 Disbursement Requirement

When a unit receives an invoice, bill, or other claim, it must perform a disbursement process before making payment. Specifically, G.S. 159-28(b) requires that

[w]hen a bill, invoice, or other claim against a local government or public authority is presented, the finance officer shall either approve or disapprove the necessary disbursement. If the claim involves a program, function, or activity accounted for in a fund included in the budget ordinance or a capital project or a grant project authorized by a project ordinance, the finance officer may approve the claim only if both of the following apply:

(1) The finance officer determines the amount to be payable.

(2) The budget ordinance or a project ordinance includes an appropriation authorizing the expenditure and either (i) an encumbrance has been previously created for the transaction or (ii) an unencumbered balance remains in the appropriation sufficient to pay the amount to be disbursed.

The finance officer may approve a bill, invoice, or other claim requiring disbursement from an intragovernmental service fund or trust or custodial fund not included in the budget ordinance, only if the amount claimed is determined to be payable. A bill, invoice, or other claim may not be paid unless it has been approved by the finance officer or, under subsection (c) of this section, by the governing board. The finance officer shall establish procedures to assure compliance with this subsection, in accordance with any rules adopted by the Local Government Commission.

G.S. 159-28(d1) further provides,

Except as provided in this section, each check or draft on an official depository shall bear on its face a certificate signed by the finance officer or a deputy finance officer approved for this purpose by the governing board (or signed by the chairman or some other member of the board pursuant to subsection (c) of this section). The certificate shall take substantially the following form:

“This disbursement has been approved as required by the Local Government Budget and Fiscal Control Act.

____________________________________

(Signature of finance officer).”

12.6.1 Disbursement Process is in Addition to the Preaudit Process

The disbursement requirement is often confused (or conflated) with the preaudit requirement. Although the processes appear similar, they are not interchangeable. G.S. 159-28 envisions that most obligations will be subject to the preaudit and the disbursement process. The disbursement process occurs when a local unit disburses public funds, that is, when the unit pays for the goods or services. By contrast, the preaudit process is triggered when goods are ordered, or a contract is entered into.

12.7 When does Disbursement Process Apply?

The disbursement process must be performed before a local government pays any bill, invoice, or other accounts payable.

12.8 Complying with the Disbursement Process

The law requires the finance officer (or a deputy finance officer designated by the governing board for this purpose) to do the following before paying a bill, invoice, or other claim that is accounted for in the budget ordinance or a project ordinance:

Verify that the amount is due and owing. If the amount claimed is not due and owing because, for example, the goods did not arrive or the services were not performed, then the finance officer or deputy finance officer may not authorize the disbursement. (Part of performing this process requires that the officer verify that the preaudit process was properly performed when the obligation was incurred. G.S. 159-181(a) makes it a Class 3 misdemeanor for any officer or employee to approve a claim or bill knowing it to be invalid.)

Make sure there is (still) an appropriation authorizing the expenditure.

Make sure sufficient funds remain in the appropriation to pay the amount due. If there is no budget appropriation for the expenditure, or more commonly, if sufficient unencumbered funds do not remain in the appropriation, the finance officer or deputy finance officer may not authorize the disbursement. The governing board must first amend the budget (or project/grant) ordinance to make (or increase) the appropriation.

Include a signed disbursement certificate on the face of the check or draft. Note that the text of the disbursement certificate varies slightly from the text of the preaudit certificate. It states, “This disbursement has been approved as required by the Local Government Budget and Fiscal Control Act.” [G.S. 159-28(d1)]. This is yet another reminder that these are two separate processes.

12.9 Exemptions from Disbursement Certificate Requirement

Certain transactions may be exempt from the disbursement certificate requirement. There are three categories of exempt transactions. The first two apply automatically. The third applies only if the LGC adopts certain rules and the local unit follows those rules.

Exemption 1: Any disbursement related to an obligation approved by the LGC. [G.S. 159-28(f)(1)]. This exemption from the disbursement certificate requirement applies to any payments related to loan agreements, debt issuances, and other leases and financial transactions subject to LGC approval and have been so approved. It also likely applies to audit contract payments. (Click here for more information on contracts subject to LGC approval).

Exemption 2: Any disbursement related to payroll or other employee benefits. [G.S. 159-28(f)(2)]. This exemption applies to payroll checks or payroll direct deposits. It also exempts any payments related to employee benefits, whether disbursed to the employee directly or to another entity on behalf of an employee.

Exemption 3: Any disbursement done by electronic funds transfer, as long as the local unit follows rules adopted by the LGC. [G.S. 159-28(f)(3)]. An electronic funds transfer is “[a] transfer of funds initiated by using an electronic terminal, a telephone, a computer, or magnetic tape to instruct or authorize a financial institution or its agent to credit or debit an account.” [G.S. 159-28(g)(2)]. A local unit cannot easily include a signed disbursement certificate on its electronic funds transfers. This exemption would eliminate the problem. It only applies, however, if the local unit follows rules adopted by the LGC governing electronic payments. The rules must ensure that the finance officer or a deputy finance officer has performed the other steps in the preaudit process before the transaction occurs. Following the LGC rules is considered a safe harbor. In other words, the law presumes compliance with the statutory disbursement requirements if a finance officer or deputy finance officer follows the LGC rules.

The LGC rules became effective on November 1, 2017, and are part of the North Carolina Administrative Code (20 NCAC 03 .0410). They require the following:

Resolution. The local unit’s governing board must adopt a resolution authorizing the unit to engage in electronic funds transfer, defined in G.S. 159-28(g) as “[a] transfer of funds initiated by using an electronic terminal, a telephone, a computer, or magnetic tape to instruct or authorize a financial institution or its agent to credit or debit an account.” A common means of making an electronic funds transfer is through an ACH (automated clearinghouse) payment. ACH payments occur when a local government gives an originating institution, corporation, or other originator authorization to debit directly from the local unit’s bank account for bill payment. The resolution should incorporate written policies for making electronic fund transfers or delegate the responsibility for creating such policies to the unit’s finance officer.

Policies and Procedures. The governing board or finance officer must adopt written policies that outline the procedures for making electronic fund transfers to disburse public funds. At a minimum, the policies must:

- ensure that the amount claimed is payable;

- ensure that there is a budget ordinance or project/grant ordinance appropriation authorizing the expenditures;

- ensure that sufficient moneys remain in the appropriation to cover the amount that is due to be paid out;

- ensure that the unit has sufficient cash to cover the payment.

The first three steps mirror those in the statute [G.S. 159-28(b)]. The last step ensures the local unit does not “bounce a check,” so to speak. There must be sufficient transferable cash in the account to cover the payment.

These exemptions apply only to the disbursement certificate requirement. A unit still must perform the other disbursement process steps before disbursing funds for (or by) one or more exempt transactions.

12.10 Penalties for Noncompliance with Disbursement Requirement

As with the preaudit, “if an officer or employee . . . pays out or causes to be paid out any funds in violation [of G.S. 159-28], that officer or employee, and the sureties on any official bond for that officer or employee, are liable for any sums so . . . disbursed.” [G.S. 159-28(e)]. The governing board must “determine, by resolution, if payment from the official bond shall be sought and if the governing body will seek a judgment from the finance officer or duly appointed deputy finance officer for any deficiencies in the amount.” [G.S. 159-28(e)]. Moreover, if a finance officer or a deputy finance officer gives a false disbursement certificate, he or she may also be held liable for the sums illegally committed or disbursed. It is a Class 3 misdemeanor, and may result in forfeiture of office, if the officer knowingly gives a false certificate. [G.S. 159-181(a)].

12.11 Governing Board Override

The governing board may approve a payment if a finance officer or deputy finance officer disapproves a bill, invoice, or other claim. However, the board may not approve payment if there is not an appropriation in the budget ordinance or a project ordinance or if sufficient funds do not remain in the appropriation to pay the amount due. The board must adopt a resolution approving the payment, which must be entered in the minutes along with the names of the members voting in the affirmative. The chairman or designated member of the board must sign the disbursement certificate. [G.S. 159-28(c)].

If the board approves payment and it results in a legal violation, each member of the board voting to allow payment is jointly and severally liable for the full amount of the check or draft. [G.S. 159-28(c)].

12.12 Forms of Payment

G.S. 159-28(d) directs that all bills, invoices, salaries, or other claims be paid by check or draft on an official depository, bank wire transfer from an official depository, electronic payment or electronic funds transfer, or cash. Wire transfers are used, for example, to transmit the money periodically required for debt service on bonds or other debt to a paying agent, who in turn makes the payments to individual bondholders. Local governments use Automated Clearing House (ACH) transactions to make retirement system contributions to the state, payroll payments, and certain other payments. The state has extended the use of the ACH system to most transfers of moneys between the state and local governments related to grant programs and state-shared revenues. A local unit may pay with cash only if its governing board has adopted an ordinance authorizing it as a payment option and specifying when it is allowed. [G.S. 159-28(d)(4)].

12.13 Dual Signature Requirement on Disbursements

G.S. 159-25(b) requires each check or draft to “be signed by the finance officer or a properly designated deputy finance officer and countersigned by another official . . . designated for this purpose by the governing board.” The finance officer’s (or deputy finance officer’s) signature attests to completion of review and accompanies the disbursement certificate described above. The second signature may be by the chair of the board of commissioners, the mayor of the municipality, the manager, or some other official. (If the governing board does not expressly designate the countersigner, G.S. 159-25(b) directs that for counties, it should be the board chair or the chief executive officer (i.e., the manager, administrator, or director of the unit).)

The purpose of requiring two signatures is internal control. The law intends that the finance officer review the documentation of the claim before signing the certificate and check. The second person can independently review the documentation before signing and issuing the check. The fact that two persons must separately be satisfied with the documentation should significantly reduce opportunities for fraud.

However, in many local government entities, the second signer does not exercise this independent review, perhaps relying on other procedures for the desired internal control. Recognizing this, G.S. 159-25(b) permits the governing board to waive the two-signature requirement (thus requiring only the finance officer’s signature or a properly designated deputy finance officer’s signature on the check) “if the board determines that the internal control procedures of the unit or authority will be satisfactory in the absence of dual signatures.”

12.13.1 Electronic Signatures

As an alternative to manual signatures, G.S. 159-28.1 permits the use of signature machines, signature stamps, or similar devices for signing checks or drafts. In practice, these are widely used in local units across North Carolina. To do so, a governing board must approve the use of such signature devices through a formal resolution or ordinance, which should designate who is to have custody of the devices. For internal control purposes, this equipment must be properly secured. The finance officer or another official given custody of the facsimile signature device(s) by the governing board is personally liable under the statute for illegal, improper, or unauthorized use of the device(s).

- 12.0 Introduction

- 12.1 The Preaudit Requirement

- 12.2 When Does the Preaudit Requirement Apply?

- 12.3 What Does the Preaudit Require?

- 12.4 Consequences for Not Complying with the Preaudit Requirements

- 12.5 A Practical Approach to Preaudit

- 12.6 Disbursement Requirement

- 12.7 When does Disbursement Process Apply?

- 12.8 Complying with the Disbursement Process

- 12.9 Exemptions from Disbursement Certificate Requirement

- 12.10 Penalties for Noncompliance with Disbursement Requirement

- 12.11 Governing Board Override

- 12.12 Forms of Payment

- 12.13 Dual Signature Requirement on Disbursements

12 Preaudits & Disbursements

Sample Ordinances and Policies

Preaudit Policy Sample

Disbursement Policy Sample

12 Preaudits & Disbursements

Implementation Tools

12 Preaudits & Disbursements

LGC Memos