Chapter 2:

Budgeting

2.0 Introduction

North Carolina counties, municipalities, and public authorities (collectively, local units) are required to budget and spend money in accordance with the Local Government Budget and Fiscal Control Act (LGBFCA), codified as Article 3 of Chapter 159 of the North Carolina General Statutes (G.S. 159, Art. 3). In fact, a local unit may not expend any funds, regardless of their source, unless the money has been properly budgeted through the annual budget ordinance, a project ordinance, or a financial plan adopted by the unit’s governing board.

A local unit may spend public funds only for public purposes specifically authorized by the state legislature, through general laws, charter provisions, or other local acts. Revenues and expenditures for the provision of general government services are authorized in the annual budget ordinance. (G.S. 159-13). Revenues and expenditures for an internal service fund are authorized in the annual budget ordinance or in a financial plan. (G.S. 159-13.1). Revenues and expenditures for capital projects or for projects financed with grant or settlement proceeds are authorized in the annual budget ordinance or in a project ordinance. (G.S. 159-13; G.S. 159-13.2).

2.1 Annual Budget Ordinance

The annual budget ordinance is the legal document that recognizes revenues, authorizes expenditures, and levies taxes for a local unit for a single fiscal year. Each unit’s fiscal year runs from July 1 through June 30. [G.S. 159-8(b)]. However, The Local Government Commission (LGC) may authorize a public authority, as defined in G.S. 159-7(10), to have a different fiscal year if it facilitates the authority’s operations. The budget ordinance must be adopted by the unit’s governing board. At its core, it reflects the governing board’s policy preferences and provides a roadmap for implementing the board’s vision for the unit.

The LGBFCA requires the board to include certain items in the budget ordinance and to follow a detailed procedure for adopting the budget ordinance. The LGBFCA also imposes certain substantive requirements and limitations on the budget ordinance.

2.1.1 Budgeting Funds

The budget ordinance is comprised of one or more funds. (G.S. 159-26). A fund is “a fiscal and accounting entity with a self-balancing set of accounts recording cash and other resources, together with all related liabilities and residual equities or balances, and changes therein, for the purpose of carrying on specific activities or attaining certain objectives in accordance with special regulations, restrictions, or limitations.” [G.S. 159-7(b)(8)]. All counties, municipalities, and some public authorities have a General Fund. For counties and municipalities, this fund comprises most of the revenues and appropriations for general government operations. Common additional budget funds include:

- Enterprise Fund. A county and municipality must budget and account for each public enterprise activity in a separate fund. The only exception is for a combined water / wastewater system, which can be included in the same enterprise fund. The public enterprises for counties are water, wastewater, solid waste, stormwater, public transportation, airports, and off-street parking. (G.S. 153A-274). The public enterprises for municipalities are water, wastewater, solid waste, stormwater, public transportation, airports, off-street parking, cable television/broadband, electric, and natural gas. (G.S. 160A–311).

- Capital Projects Fund. A local government may budget for the construction or acquisition of capital assets in a capital projects fund in the annual budget ordinance. (Alternatively, as discussed below, a local unit may adopt a separate capital budget ordinance for capital projects.)

- Special Revenue Fund. A local unit must account and budget for the following revenues and associated appropriations in a special revenue fund:

- functions or activities financed in whole or in part by property taxes voted by the people,

- service districts established pursuant to the Municipal or County Service District Acts, and

- monies budgeted in a grant project ordinance or settlement project ordinance.

If more than one function is accounted for in a voted tax fund, or more than one district in a service district fund, or more than one grant project in a project fund, separate accounts shall be established in the appropriate fund for each function, district, or project. [G.S. 159-26(b)(2)].

There are other budgetary funds that are used more rarely, including debt service fund and permanent fund. (G.S. 159-26).

2.1.2 Balanced Budget

The annual budget ordinance must be balanced. A budget ordinance is balanced when “the sum of estimated net revenues and appropriated fund balances is equal to appropriations.” [G.S. 159-8(a)]. The law requires an exact balance; it permits neither a deficit nor a surplus. Furthermore, each of the budgeting funds that make up the annual budget ordinance (e.g., general fund, enterprise fund, etc.) also must be balanced.

Balanced Budget Ordinance

Estimated net revenues is the first variable in the balanced-budget equation; it comprises the revenues a unit expects to actually receive during the fiscal year, including amounts to be realized from collections of taxes or fees levied in prior fiscal years. (Typically, debt proceeds are not considered a form of revenue, but for budgetary purposes debt proceeds that are or will become available during the fiscal year are included in estimated net revenues. But note that many projects funded with debt proceeds are budgeted in a capital project ordinance, not the annual budget ordinance.) The LGBFCA requires that a unit make reasonable estimates as to the amount of revenue it expects to receive. [G.S. 159-13(b)(7)]. A unit should have some demonstrable basis for its estimates, such as historical trends or other comparable data.

The law places a specific limitation on property tax estimates. The estimated percentage of property tax collection budgeted for the coming fiscal year cannot exceed the percentage of collection realized in cash as of June 30 during the fiscal year preceding the budget year. [G.S. 159-13(b)(6)]. The statute provides for a different calculation when budgeting for property taxes on registered motor vehicles. The percentage of collection is based on the nine-month levy ending March 31 of the fiscal year preceding the budget year, and the collections realized in cash with respect to this levy are based on the twelve-month period ending June 30 of the fiscal year preceding the budget year. Revenues must be budgeted by “major source.” [G.S. 159-13(a)]. Examples are property taxes, sales and use taxes, licenses and permits, intergovernmental revenues, charges for services, specific grant programs, and other taxes and revenues. More information on revenue sources is available in Chapter 5: Revenue Sources.

The second variable in the balanced-budget equation is appropriated fund balance. Appropriated fund balance is best understood as the amount of cash reserves needed to fill the gap between estimated revenues and appropriations. (More information on fund balance is available in Chapter 3: Fund Balance). Only a portion of a local unit’s fund balance is available for appropriation each year. The LGBFCA defines the fund balance available for appropriation as “the sum of cash and investments minus the sum of liabilities, encumbrances, and deferred revenues arising from cash receipts, as those figures stand at the close of the fiscal year next preceding the budget year.” [G.S. 159-13(b)(16)]. All these figures are estimates because the calculation is being made for budget purposes before the end of the current year. If the estimate of available fund balance is for the general fund, typical liabilities are payroll owed for a payroll period that will carry forward from the current year into the budget year. Encumbrances arise from purchase orders and other unfulfilled contractual obligations for goods and services that are outstanding at the end of a fiscal year. They reduce legally available fund balance because cash and investments will be needed to pay for the prior year payroll and the goods and services on order. (Note that as discussed in chapter 3, Fund Balance, the governing board is required to appropriate this portion of the fund balance to cover the encumbered amounts to be paid out in the budget fiscal year, but the amount is subtracted from fund balance available for new appropriations in the budget year.) Deferred revenue from a cash receipt is revenue that is received in cash in the current year, even though it is not owed to the local government until the coming budget year. Such prepaid revenues are primarily property taxes that should be included among revenues for the upcoming fiscal year’s budget rather than carried forward as available fund balance from the current to the upcoming fiscal year.

A unit’s governing board is not required to appropriate all the resulting legally available fund balance, only that which is required, when added to estimated net revenues, to equal the budgeted appropriations for the fiscal year. The remaining moneys serve as cash reserves of the unit, to be used to aid in cash flow during the fiscal year. A unit also may use unappropriated fund balance to save money to meet emergency or unforeseen needs and to be able to take advantage of unexpected opportunities requiring the expenditure of money. And some units accumulate fund balance as a savings account for anticipated future capital projects, which also helps them maintain or improve their respective credit ratings.

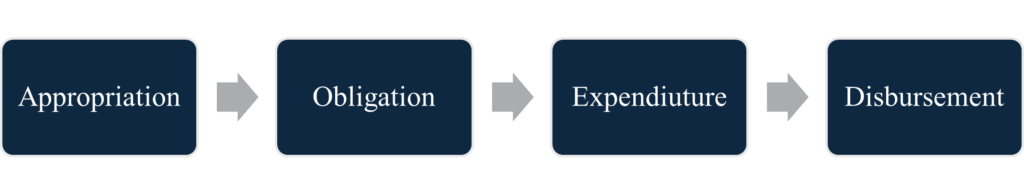

The third variable in the balanced-budget equation is appropriations for expenditures. An appropriation is a legal authorization to make an obligation and expenditure. But it is not an actual obligation or expenditure. An appropriation is a necessary predicate to incurring obligations (through contracts and agreements), expenditures, and disbursements. (An obligation is incurred when the local unit issues the Purchase Order (PO) to a vendor or executes a contract with the contractor, employee, or service provider. An expenditure happens when the goods arrive or services are performed and the payment is due by the local unit. And a disbursement is the process of making the payment.)

Appropriation & Expenditure Process

Level of Appropriation Detail

The LGBFCA allows a governing board to make appropriations in the budget ordinance by department, function, or project. [G.S. 159-13(a)]. The most common method is to appropriate by department. For example, a board may appropriate total sums to the finance department, public works department, law enforcement department, planning and zoning department, and so on. Each department then has the flexibility to fund its operational and capital expenditures from its budget allocation. Budget departments often parallel operational departments, but sometimes a local government will have a budget department that does not have an operational equivalent. For example, a local government might have a budget department for fire service but then contract for all fire service with one or more nonprofit fire departments.

The term “function” has two possible meanings for budgeting purposes. It allows a local government to group together multiple departments, such as law enforcement and fire, under a broader budgeting category of “public safety.” Alternatively, it allows a board to appropriate moneys for major expenditure categories within each department, such as salaries/benefits, utilities, supplies, insurance, capital, and the like. In this case, the budget officer/manager, department heads, and other staff may not exceed the amounts budgeted for each function category/sub-category.

The term “project” is not further defined in the statute. The best guidance for local units on how to define project for this purpose, is to look at the parallel budgeting statute, G.S. 159-13.2. That statute provides an alternative budget process and format for capital projects, grant projects, and settlement projects. According to that statute, a capital project “means a project financed in whole or in part by the proceeds of bonds or notes or debt instruments or a project involving the construction or acquisition of a capital asset.” A grant project “means a project financed in whole or in part by revenues received from the federal and/or State government for operating or capital purposes as defined by the grant contract.” And a settlement project is “a project financed in whole or in part by revenues received pursuant to an order of the court or other binding agreement resolving a legal dispute.” G.S. 159-13.2 states that a local unit has the option to budget for these type of projects either in the annual budget ordinance or a in a project ordinance. It seems reasonable to conclude then that the term “project” in the annual budget ordinance has the same meaning as a capital project, grant project, or settlement project.

Working Budgets

The budget ordinance is a summary document that, for ease of exposition, aggregates expenditures. Many governing boards require the submittal of more detailed, line-item budgets by each department to justify the expenditures being requested. A board may require the manager or head of each department over which it has direct or indirect supervisory control to follow the more detailed budgets (“working budgets”) during the fiscal year. The budget ordinance represents the legal appropriations of the unit, though.

This distinction between the annual budget ordinance and a working budget is significant, though. The annual budget ordinance represents the legal level of appropriation. The statute governing disbursements of public funds requires that before an obligation may be incurred by a unit, the finance officer or a deputy finance officer must verify that there is an appropriation authorizing that particular expenditure. [G.S. 159-28(a)]. This statute refers to an appropriation in the budget ordinance, not in a more detailed working budget.

No Appropriations to Fund Balance

A question that often arises is whether a governing board may appropriate money for savings toward future fiscal year projects or programs. North Carolina law does not allow a local government to appropriate money to fund balance. Fund balance results when either actual revenues exceed budget estimates or actual expenditures are less than budgeted appropriations in any given fiscal year. (More on fund balance in Chapter 3: Fund Balance.) As detailed below, though, a governing board may appropriate funds to a capital reserve fund to save moneys for future, specific capital projects.

2.1.3 Required Budget Ordinance Appropriations

The LGBFCA directs a governing board to include certain appropriations in its budget ordinance in addition to the balanced-budget requirement. Not that the budget ordinance requirements discussed in this policy are generally limited to those imposed by the LGBFCA. Units must be mindful that other statutory provisions may place additional requirements or restrictions on the budget ordinance. These requirements apply to the initial adoption of the budget ordinance as well as to any subsequent amendments.

Debt Service

A governing board must appropriate the full amount estimated by the local government’s finance officer to be required for debt service during the fiscal year. [G.S. 159-13(b)(1)]. During the spring, the LGC notifies each finance officer of that local government’s debt-service obligation on existing debt for the coming year. If a county or municipality does not appropriate enough money for the payment of principal and interest on its debt, the LGC may order the unit to make the necessary appropriation; if the unit ignores this order, the LGC may itself levy the local tax for debt-service purposes. (G.S. 159-36). Note that the LGC may not require a unit to make appropriations for repayment of installment-financing debt incurred under G.S. 160A-20 because of the requirement of a non-appropriation clause. The provision also does not apply to contractual obligations undertaken by a local government in a debt instrument issued pursuant to G.S. Chapter 159G unless the debt instrument is secured by a pledge of the full faith and credit of the unit.

Continuing Contracts

A governing board must make appropriations to cover any obligations that will come due during the fiscal year under a continuing contract unless the contract terms expressly authorize the board to refuse to do so in any given budget year. [G.S. 159-13(b)(15)]. Continuing contracts are those that extend for more than one fiscal year.

Fund Deficits

A governing board must make appropriations to cover any deficits within a fund from the current fiscal year. [G.S. 159-13(b)(2)]. For budgeting purposes, a deficit occurs if the amount actually encumbered exceeds appropriations within the fund. If a unit follows the provisions on expenditure control in the LGBFCA, a deficit should not occur. However, should a deficit occur, a governing board must appropriate sufficient moneys in the next fiscal year’s budget to eliminate that deficit.

Property Taxes

If a local unit levies property taxes, the governing board must do so in the budget ordinance. [G.S. 159-13(a)]. The property tax levy is stated in terms of a rate of cents per $100 of taxable value.

Encumbered Fund Balance

If a local unit incurs obligations in the prior year that have not/will not be paid during the prior fiscal year, the unit must appropriate sufficient amounts to cover those expenditures in the new fiscal year. Once the fiscal year expires, there is no budget authority to disburse funds under the prior year’s budget. The moneys must be included in the new budget ordinance before they can be disbursed. This often occurs when a unit orders goods or enters into service contracts toward the end of the fiscal year.

Some units wait until after July 1 and have the governing board amend the new annual budget ordinance to make appropriations to cover outstanding encumbrances. Other units make the appropriations with the adoption of the initial budget ordinance by reference to the encumbrances that will be outstanding as of July 1, including a provision similar to the following: “That the reserve for encumbrances at June 30, 20XX, representing prior commitments as of that date, are hereby appropriated and distributed to the departmental budgets under which obligations were incurred during the 20xx-20xx [prior year] budget year.”

2.1.4 Limits on Appropriations

Other LGBFCA provisions place upper or lower limits on certain appropriations in the budget ordinance. The statute also specifies the types of funds that may (and sometimes must) be used.

Contingency Appropriations

In each fund, a governing board may include a contingency appropriation, that is, an appropriation that is not designated to a specific department, function, or project. The contingency appropriation may not exceed 5 percent of the total of all other appropriations in the fund, though. [G.S. 159-13(b)(3)]. The governing board may delegate authority to the unit’s budget officer to assign contingency appropriations to specific departments, functions, or projects during the fiscal year. (G.S. 159-15). The budgetary changes must be reported to the board and reflected in the board’s minutes at its next regular meeting.

Property Tax Levy Limits

If a unit levies property taxes, the proceeds must be used only for statutorily authorized purposes. In addition, there is a $1.50 per $100 property valuation aggregate property-tax rate cap. [G.S. 159-13(b)(4)]. Note that G.S. 160A-209 and 153A-149 authorize a municipality and a county, respectively, to seek voter approval to levy property taxes for purposes not authorized under general law or to legally dedicate a portion of the total property tax rate to a specific purpose. If a unit receives voter approval to expend property tax proceeds for another purpose, the total appropriation must not exceed the estimated amount of the dedicated property tax proceeds plus the estimated sum of other revenue sources that will be allocated for this purpose. [G.S. 159-13(b)(5)].

And, as detailed above, there is further limit on the amount of estimated property tax levy a local unit may use in its revenue estimate. The estimated percentage of collection of property taxes used in the rate calculation may not exceed the percentage of the levy actually realized in cash as of June 30 during the prior fiscal year. For purposes of this calculation, the levy for the registered motor vehicle tax under Article 22A of Chapter 105 of the General Statutes is based on the nine-month period ending March 31 of the preceding fiscal year, and the collections realized in cash with respect to this levy is based on the 12-month period ending June 30 of the preceding fiscal year. [G.S. 159-13(b)(6)].

2.1.5 Limits on Interfund Transfers

The annual budget ordinance sometimes includes appropriations to transfer money from one fund to another. The LGBFCA generally permits appropriations for interfund transfers, but it sets some restrictions on them, each designed to maintain the basic integrity of a fund in light of the purposes for which the fund was established. In addition, the LGBFCA prohibits certain interfund transfers of moneys that are earmarked for a specific service. Each of the limitations on interfund transfers discussed below is subject to the modification that any fund may be charged for general administrative and overhead costs properly allocated to its activities as well as for the costs of levying and collecting its revenues. [G.S. 159-13(b)].

Voted Property Tax Funds

Proceeds from a voted property tax may be used only for the purpose approved by the voters. Such proceeds must be budgeted and accounted for in a special revenue fund, [G.S. 159-26(b)(2)], and generally may not be transferred to another fund, except to a capital reserve fund if appropriate. [G.S. 159-13(b)(10)]. A unit may establish and maintain a capital reserve fund to save moneys over time to fund certain designated capital expenditures. (G.S. 159-18).

Enterprise Funds

A governing board may transfer moneys from an enterprise fund to another fund only if other appropriations in the enterprise fund are sufficient to meet operating expenses, capital outlays, and debt service for the enterprise. [G.S. 159-13(b)(14)]. Note that “[a] county may, upon a finding that a fund balance in a utility or public service enterprise fund used for operation of a landfill exceeds the requirements for funding the operation of that fund, including closure and post-closure expenditures, transfer excess funds accruing due to imposition of a surcharge imposed on another local government located within the State for use of the disposal facility, as authorized by G.S. 153A-292(b), to support the other services supported by the county’s general fund.” [G.S. 159-13(b)(14)]. (Note that other statutory provisions further restrict or prohibit a unit from transferring moneys associated with certain public enterprises.) Although transferring money from an enterprise fund to another fund is legally allowed, it may result in negative consequences. It may, for example, negatively impact a local unit’s credit rating or disqualify the unit from certain state loan and grant programs. (G.S. 159G-37).

A governing board also may transfer moneys from the general fund to an enterprise fund. (G.S. 160A-313; G.S. 153A-276). Because enterprise activities should be self-sustaining, such a transfer may raise red flags for auditors, potential creditors of the public enterprise, and the LGC, about the financial viability of the enterprise.

Reappraisal Reserve Fund

A reappraisal reserve fund is established to accumulate money to finance a county’s next real property revaluation, which must occur at least once every eight years. Appropriations to a reappraisal reserve fund may not be used for any other purpose. [G.S. 159-13(b)(17)].

Service District Funds

A service district is a special taxing district of a county or municipality. Although a service district is not a separate local government unit, both the proceeds of a service district tax and other revenues appropriated to the district belong to the district. Therefore, no appropriation may be made to transfer moneys from a service district fund except for the purposes for which the district was established. [G.S. 159-13(b)(18)]. This restriction also applies to any other revenues the local unit has appropriated to the service district.

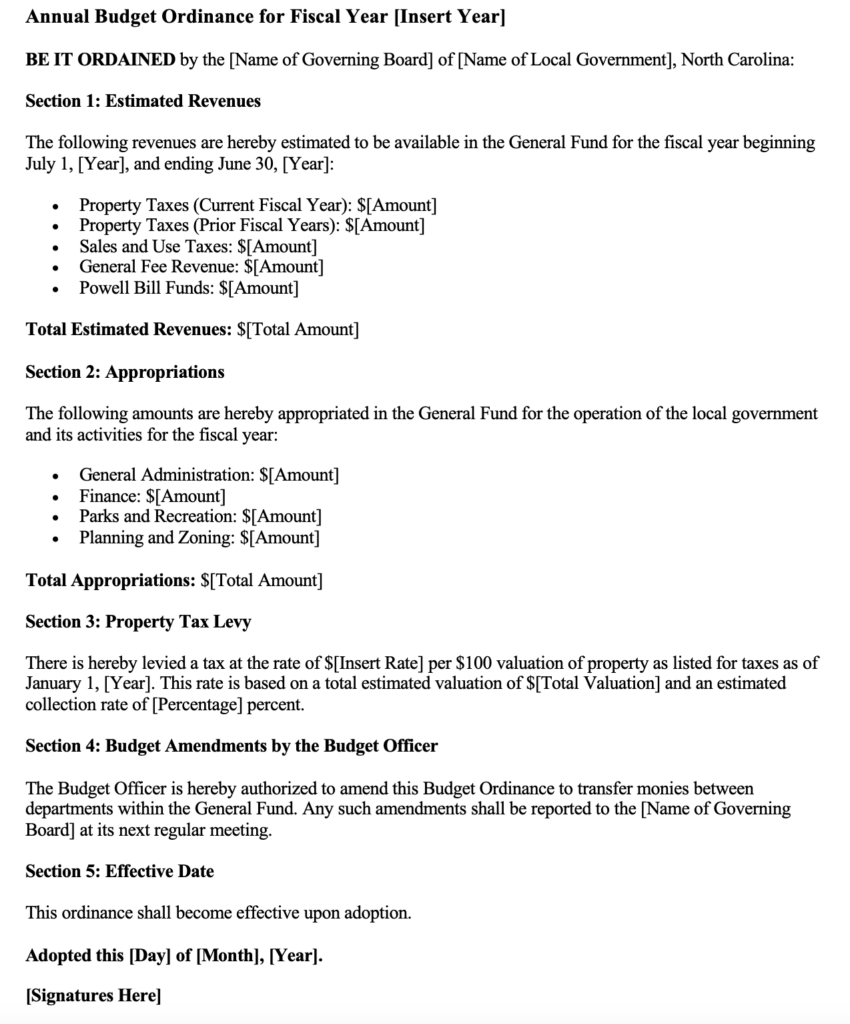

2.1.6 Minimum Annual Budget Ordinance Format

Even the smallest local governments must include a minimum amount of information to have a valid annual budget ordinance. It must include at least one fund (most likely the general fund). It must list revenues by major source. it is not enough just to list total revenues. It must make appropriations by department, function, and/or project. And it must levy any property taxes. The following depicts a minimum budget format. Note that it does not include all possible revenue sources or all possible budget departments.

2.1.7 Exclusions from Annual Budget Ordinance

There are certain items that are excluded from the annual budget ordinance–internal service funds operating under a financial plan (discussed in Section 1.12 below), items budgeted in a project ordinance (discussed in Section 2.13 below), and the revenues of certain trust and custodial funds. [G.S. 159-13(a)(3)]. Trust and custodial funds are fiduciary funds used to account for resources held by a government in a trustee or agency capacity for others. These funds are crucial for managing resources where the government has an obligation to safeguard and manage financial assets for the benefit of external parties. For example, many counties and municipalities set aside and manage moneys in a pension trust fund to finance special separation allowances for law enforcement officers. The employees and retirees for whom the local government is managing these moneys have ownership rights. Although a county or municipality must budget its initial contributions on behalf of employees into the pension trust fund, once the moneys are in the fund, earnings on the assets, payments to retirees, and other receipts and disbursements of the funds should not be included in the local government’s budget. Municipalities sometimes maintain perpetual trust funds for the care and maintenance of individual plots in the unit’s cemetery. Another example is when a county or municipality collects certain revenue for another governmental unit; it records this revenue in a custodial fund. Although the moneys are held temporarily by the county or the municipality, they belong to the other unit. The collections, therefore, are not revenues of the county or municipality collecting them and are not included in its budget ordinance.

2.1.8 Optional Working Budget Provisions

As described above, the statutes prescribe what must be included in the annual budget ordinance and the level of detail for estimated revenues and appropriations. A governing board, however, is free to include other provisions or directives in its working budget. The board might include instructions on the budget’s administration. For example, it could direct the budget officer or department heads to make obligations consistent with the object code level or line-item level of detail. The board could direct them to not expend a portion of each department’s appropriated budget. If a fund contains earmarked revenues and general revenues or supports a function for which property taxes may not be used, the board might specify the use of the earmarked funds or direct which non–property tax revenues are to support the function in question. The board may authorize and limit certain transfers among departmental or functional appropriations within the same fund. And it might and set schedules of fees to be assessed for general government services. (Note that public enterprise rate schedules must be enacted in a separate ordinance.)

2.2 Budget Officer

Before discussing the specifics of the budget process, it is important to understand the role of the budget officer. The governing board of each unit must appoint a budget officer. In a county or municipality having the manager form of government, the manager is the statutory budget officer. Counties that do not have the manager form of government may impose the duties of budget officer on the finance officer or on any other county officer or employee except the sheriff or, in counties with a population greater than 7,500, the register of deeds. Municipalities not having the manager form of government may impose the duties of budget officer on any municipal officer or employee, including the mayor if he or she consents. A public authority or special district may impose the duties on the chairperson of its governing board, on any member of that board, or on any other officer or employee. (G.S. 159-9).

The LGBFCA assigns to the budget officer the responsibility of preparing and submitting a proposed budget to the governing board each year. (G.S. 159-11). Having one official who is responsible for budget preparation focuses responsibility for timely preparation of the budget, permits a technical review of departmental estimates to ensure completeness and accuracy, and allows for administrative analysis of departmental priorities in the context of a local unit’s overall priorities. In many units, the statutory budget officer often delegates many of the duties associated with budget preparation to another official or employee, for example, the finance officer or a separate budget director or administrator. This is strictly an administrative arrangement, with the official or employee performing these duties under the direction of the statutory budget officer. Under the law, the budget officer retains full responsibility for budget preparation.

Once the budget ordinance is adopted, the budget officer is charged with overseeing its enactment. As discussed below, the governing board also may authorize the budget officer to make certain limited modifications to the budget ordinance during the fiscal year.

2.3 Budget Preparation

Before the budgeting process begins, the budget officer, often with guidance from the governing board, establishes an administrative calendar for budget preparations and prescribes forms and procedures for departments to use in formulating requests. Budget officers often include fiscal or program policies to guide departmental officials in formulating their budget requests. The LGBFCA specifies certain target dates for the key stages in the budgeting process, which should be incorporated into the budget officer’s plan.

A budget officer’s calendar often includes other steps that, though not statutorily required, are integral to an effective budgeting process. For example, many units kick off the annual budget process with one or more budget retreats or workshops for governing board members, department heads, and others. This allows governing board members to set policy for the coming year and provide directives to the budget officer and department heads about budget requests at the outset of the budget process.

Sometimes a budget officer will need to include other boards, organizations, or citizens in the budgeting process. Counties must provide funding for several functions that are (or may be) governed by other boards, such as public schools, community colleges, elections, social services, mental health, and public health. These boards have their own processes for formulating proposed budgets and requesting funds from the county. In addition, both counties and municipalities routinely receive requests from nonprofits, other private organizations, or citizens for appropriations to support certain community activities and projects. A county or municipality generally does not have legal authority to make grants to private entities (including nonprofits). The county or municipality may, however, enter into a contract with a private entity and pay it to perform a function on behalf of the local government. (G.S. 153A-449; G.S. 160A-20.1). The budget officer often serves as the liaison between these other boards, private entities, and citizen groups, and the governing board. The budget officer should work with the governing board to establish an organized process for the board to receive and evaluate these various requests.

2.4 Budget Calendar

By April 30: Departmental Requests Must Be Submitted to the Budget Officer. The LGBFCA directs that each department head submit to the budget officer the revenue estimates and budget requests for his or her department for the budget year. Each department, or the unit’s finance officer, also must submit information about current-year revenues and expenditures. The budget officer should specify the format for, and detail of, these submissions. (G.S. 159-10).

By June 1: Proposed Budget Must Be Presented to the Governing Board. The budget officer must compile each department head’s revenue estimates and budget requests and submit a proposed budget for consideration by the governing board. [G.S. 159-11(a)]. Generally the proposed budget must comply with all the substantive requirements previously discussed. A governing board, however, may request that the budget officer submit a budget containing recommended appropriations that are greater than estimated revenues. [G.S. 159-11(c)]. This affords the board a ready opportunity to discuss different expenditure options.

Between Presentation of Proposed Budget to the Governing Board and its Adoption: Notice and Public Hearing. When the budget officer submits the proposed budget to the governing board, a copy must be filed in the office of the clerk to the board, where it remains for public inspection until the governing board adopts the budget ordinance. [G.S. 159-12(a)]. The clerk must publish a statement that the proposed budget has been submitted to the governing board and is available for public inspection. [G.S. 159-12(a)]. The notice also must specify the date and time of the public hearing to be held on the budget. The LGBFCA does not specify where or when the statement must be published. The clerk should follow the general provisions for legal advertising in Article 50 of G.S. Chapter 1. The clerk also must make a copy of the proposed budget available to all news media in the county. [G.S. 159-12(a)]. It may be helpful, though it is not legally mandated, for a unit to also post the proposed budget on its website.

The governing board is required to wait at least ten days after the budget officer submits the proposed budget before adopting the budget ordinance. This is true even if the board makes no changes to the proposed budget. (G.S. 159-13). The ten-day period begins to run the day after the notice is published. Weekend days and legal holidays count toward the total number of days. However, the ten-day period may not end on a Saturday, Sunday, or legal holiday. It must instead end on the next weekday that is not a legal holiday. See Rule 6, N.C. Rules of Civil Procedure, G.S. 1A-1. This interim period affords citizens time to review the proposed budget and to voice their opinions or objections to governing board members.

The governing board also must hold at least one public hearing on the proposed budget before adopting the budget ordinance. During the public hearing any person who wishes to be heard on the budget must be allowed time to speak. [G.S. 159-12(b)]. The board should set the time and place for the public hearing when it receives the proposed budget, if not before. This information should be included in the notice published by the clerk. Sometimes a board holds a series of budget review meetings and briefings on each of the major budget categories. These do not satisfy the statutory requirement. The law requires that at least one public hearing be held on the entire budget. The statute requires no specific minimum number of days between the date on which the notice appears and the date on which the hearing is held; however, the notice should be timely enough to allow for full public participation at the hearing.

By July 1: Governing Board Must Adopt Budget Ordinance. After the governing board receives the proposed budget from the budget officer, it is free to make changes to the budget before adopting the budget ordinance. In fact, based on citizen input, as well as that from other boards and department heads, the governing board often makes adjustments to the proposed budget before finalizing and adopting the budget ordinance. Questions often arise when a board makes changes to the proposed budget about whether and to what extent it must make the changes known to the public before adopting the budget ordinance. The statute requires only that the budget officer’s proposed budget be made available for public inspection and that one public hearing be held after the proposed budget is submitted to the board. A unit is under no legal obligation to provide notice or solicit public input of modifications to the proposed budget before its adoption.

2.5 Budget Message

When the budget officer submits the proposed budget to the governing board, he or she must include a budget message. [G.S. 159-11(b)]. The message should contain a summary explanation of the unit’s goals for the budget year. It also should detail important activities funded in the budget and point out any changes from the previous fiscal year in program goals, appropriation levels, and fiscal policy.

2.6 Revenue-Neutral Tax Rate

If a revaluation of real taxable property in the unit occurs in the year preceding the budget year, the budget officer must include in the proposed budget a statement of the revenue-neutral tax rate, “the rate that is estimated to produce revenue for the next fiscal year equal to the revenue that would have been produced for the next fiscal year by the current tax rate if no reappraisal had occurred.” [G.S. 159-11(e)]. While the LGBFCA is silent on where the revenue-neutral tax rate must be included in the proposed budget, an appropriate place would be the budget message. The rate is calculated as follows:

- Determine a rate that would produce revenues equal to those produced for the current fiscal year.

- Increase the rate by a growth factor equal to the average annual percentage increase in the tax base due to improvements since the last general reappraisal.

- Adjust the rate to account for any annexation, de-annexation, merger, or similar events.

To expand on the growth factor, most tax bases increase due to new construction and the accumulation of personal property by taxpayers. Absent a revaluation, the current tax base can be expected to increase by the average growth rate over the past several years. This means that even if the tax rate were kept constant, next year’s tax levy would be larger than this year’s tax levy. A revenue-neutral rate must be increased by an average annual growth factor to account for this expected natural growth in the tax base and tax levy. Remember that the revenue-neutral rate represents the tax rate that, when applied to the newly revalued tax base, is estimated to produce the same tax levy as would have been produced next year using the current year’s tax rate if a revaluation had not occurred. If a revenue-neutral rate were not increased by an average annual growth factor of the tax base, the calculation would understate the tax levy that would be produced without the revaluation in the coming fiscal year.

REVENUE NEUTRAL TAX CALCULATION WORKSHEET

2.6.1 Revenue Neutral Calculations in Municipalities that Lie in Multiple Counties

A municipality that lies in multiple counties must calculate a new revenue neutral rate whenever any of those counties conducts a revaluation. In addition to needing to calculate its RN rate more frequently, a multi-county municipality faces a particular challenge with that portion of the revenue neutral calculation that requires the municipality to determine the growth rate of its tax base in between county revaluations. This growth is the “regular” increase in a municipality’s tax base due to new construction and purchases of equipment, cars, and other taxable personal property.

For a one-county municipality, the growth rate calculation is relatively simple. The municipality determines the change in its tax base in between each non-revaluation year and then averages those changes to get its overall growth rate since the last revaluation. This calculates the average increase or decrease in its tax base between years in which the county does not conduct a revaluation. A multi-county municipality should calculate its growth rate back to the last revaluation by any county in which the municipality lies, not back to the last revaluation by the county that conducted the current revaluation. For multiple-county municipalities, the most recent revaluation is often one conducted by a county different from the county conducting the current revaluation. But not always. If the revaluation cycle of one of those counties is contained entirely within the other county’s revaluation cycle, the growth rate can be calculated as usual.

2.7 Annual Budget Ordinance Adoption

The LGBFCA allows a budget ordinance to be adopted at any regular or special meeting, at which a quorum is present, by a simple majority of those present and voting. (G.S. 159-17). It should be noted that the adoption of the budget ordinance is not subject to the normal ordinance-adoption requirements of G.S. 153A-45 for counties and G.S. 160A-75 for municipalities. The board must provide sufficient notice of the regular or special meeting, according to the provisions in the applicable open meetings law. (G.S. 143-318.12). However, G.S. 159-17 specifies that “no provision of law concerning the call of special meetings applies during [the period beginning with the submission of the proposed budget and ending with the adoption of the budget ordinance] so long as (i) each member of the board has actual notice of each special meeting called for the purpose of considering the budget, and (ii) no business other than consideration of the budget is taken up.” The budget ordinance is entered in the board’s minutes, and within five days of its adoption, copies are to be filed with the budget officer, the finance officer, and the clerk to the board. [G.S. 159-13(d)]. Once the board adopts the budget ordinance, it may not repeal it. Any modifications are made pursuant to G.S. 159-15. This is true even if the board adopts the budget ordinance before July 1.

2.8 Interim Budget Appropriations

After June 30, a unit has no authority to make expenditures (including payment of staff salaries) under the prior year’s budget. If a board does not adopt the new budget ordinance by July 1 and needs to make expenditures, it must make “interim appropriations for the purpose of paying salaries, debt-service payments, and the usual ordinary expenses” of the unit until the budget ordinance is adopted. (G.S. 159-16). This is a stopgap measure. It is not a budget, but it is often referred to as an interim budget. It may not include appropriations for salary and wage increases, capital items, and program or service expansion. It may not levy property taxes. The purpose of an interim budget is to temporarily keep operations going at current levels. An interim budget need not include revenues to balance the appropriations. All expenditures made under an interim budget are charged against the comparable appropriations in the annual budget ordinance once it is adopted. In other words, the interim expenditures eventually are funded with revenues included in the adopted budget ordinance.

SAMPLE INTERIM BUDGET ORDINANCE

2.8.1 Impact on Property Tax Collections

Recall that all property taxes (including special taxing district taxes) are levied with the adoption of the annual budget ordinance. Most tax offices mail their property tax bills in July or August. But this can’t happen unless the government has adopted is annual budget ordinance to set its tax rate(s) for the new fiscal year. If those tax bills are delayed due to the adoption of interim appropriations, there may be negative consequences for the local unit and its taxpayers.

Some jurisdictions offer discounts for paying property taxes before a certain deadline. All discounts that are offered must end by the statutorily required deadline of September 1. Many taxpayers across the state make it a practice to pay before September 1 to take advantage of their local governments’ discount; they may lose this opportunity if the annual budget ordinance is not adopted in time. Of course, taxpayers are always permitted to pre-pay their estimated property taxes before bills are issued. These pre-payments must receive the discount if they are made before September 1. However, pre-payments create uncertainty for both the tax office and the taxpayer because no one knows whether the correct amount has been paid until the tax rate is finally adopted. The resulting refunds or additional collections required if the tax rate changes from that used to calculate the estimated pre-payments will require additional staff time and may cause significant confusion for taxpayers.

Delaying tax bills also means delaying tax payments from the many taxpayers who pay shortly after receiving their bills. This delay could have negative consequences for the local government’s revenue stream and might create a cash crunch depending on how long the delay lasts.

In the many counties that collect property taxes for one or more municipalities, conflicts could arise if a municipality is significantly delayed in adopting its annual budget ordinance. It could cause the county to have to delay sending its tax bill or require it to send multiple tax bills. At a minimum, this adds to the confusion for taxpayers and also adds significant costs.

The North Carolina Department of Revenue (NCDOR) expects all local governments to report their new property tax rates for the new fiscal year by mid- to late-July so that the North Carolina Division of Motor Vehicles (NCDMV) can include those rates on the “invitations to renew” (aka property tax bills) for motor vehicle registrations that expire at the end of October. The renewal notices go out roughly 90 days before the registrations expire. Remember that the property tax rate for registered motor vehicles (RMV) must be same as that for all other property in a jurisdiction; local governments are not permitted to adopt different tax rates for different types of property.

Assume the new property tax rate is higher than the previous year’s rate. A taxpayer who mails a renewal check that is received by the NCDMV after the new rate is entered will have their payment rejected because the new RMV bill amount exceeds the old bill amount listed on the renewal notice. The NCDMV will deposit the check and eventually send a refund, but until the taxpayer sends a new check in the correct amount the taxpayer will not receive a registration renewal and risks interest and penalties on her late registration and tax payment. And the taxpayer will at least temporarily have to pay twice, once with the original check that was in the wrong amount and once with the second check in the correct amount.

If the new tax rate is lower than the previous year’s rate, the NCDMV will accept the payment and process the renewal. Overpayments of over $5 will be refunded by the NCDMV; overpayments of under $5 are not refunded but instead “donated” to the state highway fund.

Similar confusion will arise for taxpayers who attempt to pay online or in person at a NCDMV office after the local unit’s tax rate changes, because the amount demanded by the NCDMV may not match the amount on taxpayer’s renewal notice. Taxpayers who pay in person at a license plate agency (“LPA”) operated by a third-party may wind up paying the old bill amount, because LPA’s usually don’t check the RMV taxation system to update billing records prior to accepting payment. If that occurs, counties will have to refund any overpayments but will not be able to recoup any underpayments due to the fact that all local government collection remedies for RMV taxes were eliminated as part of the Tag & Tax Together system.

2.8.2 LGC Action for Failure to Adopt a Budget Ordinance

At some point, if a local unit’s governing board refuses or is unable to adopt its budget ordinance, the LGC may take action. State law empowers the LGC to “assume full control” of a unit’s financial affairs if the unit “persists, after notice and warning from the [LGC], in willfully or negligently failing or refusing to comply with the provisions” of the LGBFCA. [G.S. 159-181(c)]. If the LGC takes this action, it becomes vested “with all of the powers of the governing board as to the levy of taxes, expenditure of money, adoption of budgets, and all other financial powers conferred upon the governing board by law.” (G.S. 159-181). LGC takeover will only occur in extreme cases, though. Most of the time, a unit’s governing board is left to work out any differences and adopt its budget ordinance.

2.9 Budget Adoption Violations

As detailed above, there are several process and substantive requirements for adopting the annual budget ordinance. Failing to follow any of the legal requirements results in a statutory violation that may be reflected in the local unit’s audit and be flagged by the LGC, lenders, and others as compliance deficiencies. There are no automatic statutory penalties for these violations. And not all violations will invalidate the annual budget ordinance. For example, if a local unit fails to comply with the deadline for presenting the proposed budget to the board by the statutory deadline, that is unlikely to impact the validity of the final budget ordinance. Other violations may lead to a different result, though. Failure to hold a public hearing or adopt a balanced budget ordinance, for example, could very well lead a court to determine that the budget ordinance is invalid.

2.10 Budgetary Accounting

G.S. 159-26 requires local units to maintain an accounting system with applicable funds as defined by generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP). Local units enter their adopted annual budgets into their accounting systems at the beginning of the fiscal year; this allows them to accurately track the difference between an appropriation and the accumulated expenditures and encumbrances applied against that appropriation. Budgetary accounting is considered a best practice for several reasons. It provides the foundation for budget-to-actual variance reports, providing critical information to departments for remaining within their budgets and to elected officials who possess the ultimate fiduciary responsibility of the organization. It also provides the information needed for managing budget amendments and for complying with the pre-audit requirement. (See Chapter 12: Preaudits and Disbursements Policy for more information on the pre-audit requirement.) Finally, it provides the needed information for following GAAP when local units issue their annual financial statements.

2.11 Annual Budget Ordinance Amendments

The adopted annual budget ordinance encompasses a unit’s legal authority to make all expenditures during the fiscal year. Before a unit may incur an obligation (order goods, enter into service contracts, or otherwise make legal commitments to expend public funds), the finance officer or a deputy finance officer must ensure that there is an appropriation authorizing the expenditure and that sufficient moneys remain in the appropriation to cover the expenditure. [G.S. 159-28(a)]. (This is known as the pre-audit process and is discussed in detail in Chapter 12: Preaudits and Disbursements Policy.) Events during a fiscal year may cause greater or less spending than anticipated for some activities, or needs may arise for which there is no appropriation or for which the existing one is exhausted. New revenues may become available or revenue estimates require adjustment. To address these situations the local unit may need to amend the budget ordinance.

The budget ordinance may be amended at any time after its adoption. (G.S. 159-15). Sometimes a board adopts the budget ordinance before July 1. The budget ordinance is not effective until July 1; however, it may be amended at any time after its adoption, even before July 1, subject to the limitations set forth in G.S. 159-15. A governing board may modify appropriations for expenditures, recognize additional revenue, and/or appropriate fund balance to cover new expenditures. As amended, however, the budget ordinance must continue to be balanced and comply with the other substantive requirements previously discussed. That necessarily means that the budget amendments themselves must be balanced.

2.11.1 Required and Optional Amendments

A budget amendment is required under certain circumstances:

- If a budgetary department, function, or project will exceed its budget appropriation;

- If the local unit wishes to appropriate monies to fund a new project or activity, not accounted for in the original budget ordinance;

- If the local unit receives additional revenues during the fiscal year that were not included in the original budget ordinance estimate and the board wishes to spend these revenues this fiscal year;

- If the local unit wishes to reduce an appropriation to a particular department, function, or department; and

- If the local unit wishes to move monies between appropriations within or between funds.

A budget amendment is not required for overages in object codes or line items contained in the unit’s working budget, only if more money is needed at the department, function, or project level.

Perhaps surprisingly, a budget amendment is not legally required if the local unit receives less revenues during the fiscal year than it included in its original estimate. A local unit is highly encouraged to periodically make budget amendments to update its revenue estimates and make corresponding appropriation changes if it receives less revenues during the fiscal year than originally budgeted. Otherwise, the unit risks overspending its resources.

2.11.2 Prohibitions and Limitations on Budget Amendments

Although there is broad authority to amend the budget ordinance any time after it is adopted, there are some limitations and prohibitions, specifically related to the tax rate, board member compensation, and county appropriations to school administrative units. These limitations apply once the budget ordinance is adopted, even if that occurs before July 1.

Tax Rate Changes

Local government units are limited in their ability to legally change the property tax levy or otherwise alter a property taxpayer’s liability once the annual budget ordinance has been adopted. The property tax levy includes the general property tax rate plus any special taxing district rates. A board may alter the property tax levy only if one of the following criteria are met:

- it is ordered to do so by a court;

- it is ordered to do so by the LGC; or

- the unit receives revenues that are substantially more or less than the amount anticipated when the budget ordinance was adopted. A board may change the tax levy under the third exception only if it does so between July 1 and December 31. (G.S. 159-15).

County and Municipal Board Member Compensation

A county board of commissioners sets its own “salaries, allowances, and other compensation . . .,” (see G.S. 153A-28 and G.S. 153A-92), but G.S. 153A-28 specifically provides that county board members’ compensation and allowances be set “by inclusion [in] …and adoption of the budget ordinance.” Similarly, G.S. 160A-64 provides that a municipal council “may fix its own compensation and the compensation of the mayor and any other elected officers of the city by adoption of the annual budget ordinance . . . .” These statutory provisions constitute exceptions to a governing board’s broad amendment powers in G.S. 159-15—prohibiting county and municipal governing boards from altering their own compensation during the fiscal year. A board of county commissioners or municipal council may not amend its unit’s budget to increase or decrease board members’ compensation after the budget ordinance is adopted.

The North Carolina Attorney General has issued two opinion letters supporting this interpretation of the relevant statutory provisions. In the first opinion letter, issued in 1972, the Attorney General opined on whether a county board could amend the county budget to raise or lower board members’ compensation at any time during the fiscal year. Interpreting former statutory provisions governing board member compensation, the opinion concluded that the statutory language stating that the “compensation and allowances of the chairmen and commissioners may be fixed by the board of publication in and adoption of the annual budget ordinance” confined the commissioners’ authority to fix their compensation to the time required by statute for the publication and adoption of the annual budget ordinance. 42 N.C.A.G. 132 (1972). In 1976, the Attorney General issued a letter opinion construing “G.S. 160A-64 as placing a restriction on the governing body, to-wit, the compensation can only be fixed by publication in and adoption of the annual budget ordinance, as provided in Chapter 159 of the General Statutes, the Local Government Budget and Fiscal Control Act, which requires the budget to be adopted not later than July 1 of each year.” 46 N.C.A.G. 118 (1976).

There is one exception to this general prohibition on amending the budget ordinance to alter board member compensation. A county board of commissioners may appoint the chairman or other member of the board to serve as the county manager on an interim or full-time basis. (G.S. 153A-81; G.S. 153A-84). If a commissioner agrees to serve in this capacity, his or her compensation and allowances may be increased during the fiscal year to reflect the new duties. (G.S. 153A-28). Similarly, in municipalities “having a population of less than 5,000 according to the most recent official federal census, the mayor and any member of the council shall be eligible for appointment by the council as department head or other employee, and may receive reasonable compensation for such employment, notwithstanding any other provision of law.” (G.S. 160A-158).

Note also that there is a further statutory restriction on decreasing county elected officials’ compensation, even if the change is adopted in the annual budget ordinance. A county board of commissioners “may not reduce the salary, allowances, or other compensation paid to an officer elected by the people for the duties of his elective office if the reduction is to take effect during the term of office for which the incumbent officers has been elected, unless the officer agrees to the reduction or unless the Local Government Commission… orders a reduction.” (G.S. 153A-92). This provision likely prohibits a county board of commissioners from decreasing individual commissioner’s salaries or stipends during their current term of office, even by majority vote, unless the individual commissioners agree to the reduction.

Municipal council members are not subject to the same restriction. The “salary of an elected officer other than a member of the council may not be reduced during the then-current term of office unless he agrees thereto.” (G.S. 160A-64 (emphasis added)). Thus, a municipal board may reduce council members’ salaries, if adopted in the annual budget ordinance, without their individual consent. Note that the exception likely does not apply to mayors, though. Recall that G.S. 160A-64 states that “[t]he council may fix its own compensation and the compensation of the mayor . . .” referencing council members and mayors separately. The provision that exempts the council from reducing the salary of an elected official only exempts “member[s] of the council.” It is silent with respect to mayors. It is not entirely clear whether the General Assembly intended the reference to members of the council in this context to include mayors. Based on the plain language of the statute, though, it is likely that a municipal board is not authorized to reduce a mayor’s compensation during the current mayor’s term of office, absent the mayor’s express consent.

County Appropriations to Local School Administrative Units

A county is legally required to provide both operational and capital funding to its local school administrative unit(s) (traditional public schools). The LGBFCA prohibits a county from reducing it’s appropriation to a local school administrative unit unless it is agreed to by the local school board or unless is it is part of general county-wide reduction due to prevailing economic conditions. Before a board of county commissioners may reduce appropriations to a school administrative unit as part of a general reduction in county expenditures required because of prevailing economic conditions, it must do both of the following:

- Hold a public meeting at which the school board is given an opportunity to present information on the impact of the reduction.

- Take a public vote on the decision to reduce appropriations to a school administrative unit. [G.S. 159-13(b)(9)].

A municipality is authorized, but not required, to provide funding to its public schools, according to the terms in G.S. 160A-700. If it chooses to provide funding, it is not subject to the budgetary limitations that apply to county governments.

2.11.3 Amendment Format

There is no specific format for a budget ordinance amendment. In practice, some units readopt the full budget ordinance with the changes. Other units adopt an ordinance only reflecting specific changes to account codes within the budget ordinance. Regardless of the format, the local government must retain all budget amendment documentation and regularly update its accounting system to reflect the changes.

2.11.4 Amendment Process

A budget ordinance may be amended by action of a simple majority of governing board members present at the meeting and voting, so long as there is a quorum. (G.S. 159-17). As with the requirement for budget adoption, that is a lower voting requirement than for most other ordinances, which typically require a majority of all board members. There are no notice or public hearing requirements.

2.11.5 Amendment Timing

The board must amend the budget ordinance to increase the appropriation before the local unit obligates the funds. The timing is important. It is a budget violation to incur and obligation (e.g., issue a P.O., execute a contract, etc.) if there are not sufficient funds remaining in a budget appropriation, after subtracting all outstanding encumbrances.

2.11.6 Delegation of Amendment Authority

A governing board may delegate to the budget officer the authority to make certain changes to the budget. This authority is limited to:

- transfers of moneys from one appropriation to another within the same fund, and/or

- allocation of contingency appropriations to certain expenditures within the same fund. [G.S. 159-15; G.S. 159-13(b)].

All other changes to the budget ordinance, including any changes to estimated revenues, and appropriated fund balance, and transfers between funds must be made by the governing board.

2.12 Year-End Closeout of Annual Budget Ordinance

An annual budget ordinance is only effective for a single fiscal year. It expires on July 1; it cannot authorize any obligations or disbursements after that date. Some transactions cross fiscal years, though. A local government may order goods in June that are not delivered until July. Or the goods may arrive in June but payment is not due until July. In both these cases, the local government authorized the obligation based on the budget appropriation for the fiscal year in which the goods were ordered. However, that budget appropriation expired before disbursement was due. And the monies encumbered to pay for the obligations reverted to fund balance on July 1. The local government may not perform the statutory disbursement process without a valid budget appropriation. (More on the disbursement process in Chapter 7: Preaudits and Disbursements Policy.) To address this situation, the governing board must re-appropriate the monies (carry-over funds) in the new annual budget ordinance. This is usually accomplished in an amendment or series of amendments to the new budget ordinance early in the fiscal year.

Some units process amendments after the close of the fiscal year to the prior years’ budget. These amendments are allowed and can be reflected in the year end financial report. However, such amendments have no legal significance. They cannot retroactively cure a budget violation that occurred prior to the end of the fiscal year. And they are not sufficient to avoid a preaudit violation (discussed in Chapter 7: Preaudits and Disbursements Policy).

2.13 Financial Plans for Internal Service Funds

An internal service fund may be established to account for a service provided by one department or program to other departments in the same local unit and, in some cases, to other local governments. A service often accounted for in an internal service fund is fleet maintenance. If a local unit uses an internal service fund, the fund’s revenues and expenditures may be included either in the annual budget ordinance or in a separate financial plan adopted specifically for the fund. [G.S. 159-8(a), G.S. 159-13.1].

2.13.1 Adopting a Financial Plan

The governing board must approve any financial plan adopted for an internal service fund, with such approval occurring at the same time the board enacts the annual budget ordinance. At the same time he or she submits the proposed budget to the governing board, the budget officer must also submit a proposed financial plan for each intragovernmental service fund that will be in operation during the budget year. The financial plan also must follow the same July 1 to June 30 fiscal year as the budget ordinance. An approved financial plan is entered into the board’s minutes, and within five days after its approval, copies of the plan must be filed with the finance officer, the budget officer, and the clerk of the board.

2.13.2 Balanced Financial Plan Requirement

A financial plan must be balanced. This is accomplished when estimated expenditures equal estimated revenues of a fund. (G.S. 159-13.1). Internal service fund revenues are principally charges to county, municipality, or authority departments that use the services of an internal service fund. These charges are financed by appropriated expenditures of the using departments in the annual budget ordinance. Internal service fund revenues or other resources also may include an appropriated subsidy or transfer unrelated to specific internal service fund services, which would come from the general fund or some other fund to be shown as a transfer in, rather than as revenue for the internal service fund. Expenditures from an internal service fund are typically for items necessary to provide fund services, including salaries and wages; other operating outlays; lease, rental, or debt service payments; and depreciation charges on equipment or facilities used by the fund.

In adopting the annual financial plan for an internal service fund, a governing board must decide what to do with any available balance or reserves remaining from any previous year’s financial plan. The law permits fund balance or reserves to be used to help finance fund operations in the next year or, if the balance is substantial, to fund long-term capital needs of the fund. Alternatively, the fund balance may be allowed to continue accumulating for the purpose of financing major capital needs of the fund in the future, or it may be transferred to the general fund or another fund in the budget ordinance or to a project/grant ordinance for an appropriate use. A unit should avoid amassing in its financial plans large fund balances that are unrelated to the specific needs of the internal service fund.

2.13.3 Amending a Financial Plan

A financial plan may be modified during the fiscal year, but any change must be approved by the governing board. [G.S. 159-13.1(d)]. Any amendments to a financial plan must be reflected in the board’s minutes, with copies filed with the finance officer, the budget officer, and the clerk of the board.

2.14 Project Ordinances

In North Carolina, local units may budget revenues and expenditures for the construction or acquisition of capital assets (capital projects), for projects that are financed in whole or in part by federal or state grants (grant projects), or for projects funded by settlement proceeds (settlement projects), either in the annual budget ordinance or in one or more project ordinances. A project ordinance appropriates revenues and expenditures for however long it takes to complete the capital, grant, or settlement project rather than for a single fiscal year. (G.S. 159-13.2).

2.14.1 Types of Project Ordinances

There are three types of project ordinances—capital project ordinance, grant project ordinance, and settlement project ordinance.

Capital Project Ordinance

The Local Government Budget and Fiscal Control Act (LGBFCA) defines a capital project as a project that (1) is financed at least in part by bonds, notes, or debt instruments or (2) involves the construction or acquisition of a capital asset. Although a capital-project ordinance may be used to recognize revenues and appropriate expenditures for any capital project or asset, it typically is used for capital improvements or acquisitions that are large relative to the annual resources of the unit, that take more than one year to build or acquire, or that recur irregularly. Expenditures for capital assets that are not expensive relative to a unit’s annual budget or that happen annually usually can be handled effectively in the budget ordinance.

SAMPLE CAPITAL PROJECT ORDINANCE

Grant Project Ordinance

A grant-project ordinance may be used to budget revenues and expenditures for operating or capital purposes in a project financed wholly or partly by a grant or settlement funds included in a grant contract from the federal government, the state government, or a private entity. This budgeting vehicle is most appropriate for multi-year grants, but it can be used even for single-year grants and may provide better documentation for grant compliance than the annual budget ordinance. A grant-project ordinance should not be used to appropriate state-shared taxes provided to a unit on a continuing basis, though. Such revenue or aid, even if earmarked for a specific purpose, should be budgeted in the annual budget ordinance.

SAMPLE ARPA GRANT PROJECT ORDINANCE 1

SAMPLE ARPA GRANT PROJECT ORDINANCE 2

SAMPLE FEMA GRANT PROJECT ORDINANCE

Settlement Project Ordinance

A settlement project is a project financed in whole or in part by revenues received pursuant to an order of the court or other binding agreement resolving a legal dispute. A local government may use a settlement ordinance to budget these funds.

For example, as part of nationwide settlements (and bankruptcy resolutions) with major opioid manufacturers, distributors, and retailers, North Carolina local governments are expected to receive over $1.164 billion in funding over an 18-year period, beginning in FY 2022-2023, to address the ongoing impacts of the opioid epidemic in their communities (collectively “opioid settlement funds”). All 100 counties and the following municipalities will receive the opioid settlement funds: Asheville, Canton, Cary, Charlotte, Concord, Durham, Fayetteville, Gastonia, Greensboro, Greenville, Henderson, Hickory, High Point, Jacksonville, Raleigh, Wilmington, and Winston-Salem. The schedule of payments is available at CORE-NC: Community Opioid Resources Engine for North Carolina. Local governments executed a Memorandum of Agreement (NC MOA) with the State regarding the use of the funds and certain process, compliance, and reporting requirements. Additionally, the Local Government Budget and Fiscal Control Act, G.S. Ch. 159, Art. 3, and other related state law provisions govern the budgeting, contracting, accounting, disbursement, and management of these funds.

SAMPLE OPIOID SETTLEMENT PROJECT ORDINANCE

Some local governments will receive opioid settlement funds from other settlements. These monies must be budgeted and accounted for separately (separate settlement project ordinance(s) and separate special revenue fund(s)) from those covered by the NC MOA.

2.14.2 Adopting a Project Ordinance

A governing board may adopt a project ordinance at any regular or special meeting by a simple majority of board members so long as a quorum is present. This can be done at any time during the year. The ordinance must (1) clearly identify the project and authorize its undertaking, (2) identify the revenues that will finance the project, and (3) make the appropriations necessary to complete the project. A local unit should adopt a separate project ordinance for each capital project or each grant. Each project ordinance must be entered in the board’s minutes, and within five days after its adoption copies of the ordinance must be filed with the finance officer, the budget officer, and the clerk to the board.

The budget officer also must provide certain information about project ordinances in the proposed annual budget submitted to the governing board each year. Specifically, the budget officer must include information on any project ordinances that the unit anticipates adopting during the budget year. The proposed budget also should include details about previously adopted project ordinances that likely will have appropriations available for expenditure during the budget year. [G.S. 159-13.2(f)]. This is purely informational. The board needs to take no action to reauthorize a project ordinance once it is adopted.

2.14.3 Balanced Project-Ordinance Requirement

The LGBFCA requires a capital or grant project ordinance to be balanced for the life of the project. A project ordinance is balanced when “revenues estimated to be available for the project equal appropriations for the project.” [G.S. 159-13.2(c)].

Estimated revenues for a project ordinance may include bond or other debt proceeds, federal or state grants, revenues from special assessments or user fees, other special revenues, and annually recurring revenues. As with the annual budget ordinance, debt proceeds are treated as revenues for budgeting purposes. A local unit may include debt proceeds that it reasonably expects to receive to fund a project. If a bond issuance requires voter approval and/or LGC approval, it likely is not reasonable to include the debt proceeds in the revenue estimate until the local unit has obtained those approvals. If property tax revenue is used to finance a project ordinance, it must be levied initially in the annual budget ordinance and then transferred to the project ordinance. Other annually recurring revenues may be budgeted in the annual budget ordinance and transferred to a project ordinance or appropriated directly in a project ordinance.

Appropriations for expenditures in a capital project ordinance may be general or detailed. A project ordinance may make a single, lump-sum appropriation for the project authorized by the ordinance, or it may make appropriations by line item, function, or other appropriate categories within the project. Appropriations in a grant-project ordinance should be specific enough to align with applicable grant-compliance requirements. For federal grants, that likely requires appropriations to occur at the cost-item level for each project.

The key characteristic of a project ordinance is that it has a project life, which means that the balancing requirement for such an ordinance is not bound by or related to any fiscal year or period. Estimated revenues and appropriations in a project ordinance must be balanced for the life of the project but do not have to be balanced for any fiscal year or period that the ordinance should happen to span.

2.14.4 Amending a Project Ordinance

A project ordinance may be amended at any time after its adoption but only by the governing board. [G.S. 159-13(e)]. If expenditures for a project exceed the ordinance’s appropriation, in total or for any expenditure category for which an appropriation was made, an amendment to the ordinance is necessary to increase the appropriation and identify additional revenues to keep the project ordinance balanced. A board also may amend a project ordinance to change the nature or scope of the project(s) being funded.

2.14.5 Closing Out a Project Ordinance

Unlike the annual budget ordinance, a project ordinance does not have an end date. It remains in effect until the project is finished or abandoned. There are no formal procedures for closing out a project ordinance when a project is done. Projects sometimes are completed with appropriated revenues remaining unspent. Practically speaking, such excess revenues are equivalent to a project fund balance. The remaining moneys should be transferred to another appropriate project, fund, or purpose at the project’s completion. Annual revenues budgeted in a project ordinance that remain after a project is finished may be transferred back to the general fund or to another fund included in the annual budget ordinance. Bond proceeds remaining after a project is finished should be transferred to the appropriate fund for other projects authorized by the bond order or to pay debt service on the bonds. Note that any earmarked revenues in a project ordinance retain the earmark when transferred to another project or fund.

2.15 Capital Reserve Fund

A tool available to local units to help them save for future capital projects is the capital reserve fund (CRF). A local unit may establish and maintain a CRF for any capital project in which it is authorized to engage. (G.S. 159-18, G.S. 159-48). A CRF is essentially a savings account, but a governing board may only use it to accumulate funds for specified future capital projects. It may not be used for more generalized savings or for an emergency reserve.